- Home

- Walter Moers

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures Page 7

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures Read online

Page 7

This had no real effect on the one-eyed monsters’ voracious habits, because they had ways and means of making their prey twitch if they thought it necessary. The only place they steered well clear of was Smyke’s pool, the source of the evil-smelling slime.

Rumo was proud of being the only one in the cave with a potent antidote to fear: he could go to see Volzotan Smyke and be transported into another world. Words were so incredibly powerful! Although many still meant nothing to him and were simply meaningless sounds, others had barely escaped Smyke’s lips when they became transformed into marvellous images that filled Rumo’s head and drove his fear away. Sometimes, when Smyke was telling an especially interesting story, image succeeded image until the flood of impressions transported Rumo far away into other, better times. Smyke had an answer to every question, sometimes satisfying, sometimes productive of even greater bewilderment, but even bewilderment was preferable to frozen despair.

Netherworld

One evening, when some Demonocles had behaved even more barbarously than usual and torn a piglet to pieces before Rumo’s eyes, his feeling of impotence threatened to turn into uncontrollable panic. Dark questions took shape in his head. Unable to answer them himself, he went to see Smyke.

‘What’s new, Rumo?’ asked Smyke. He propped his head on the edge of the pool like a lazy seal while the rest of his body remained hidden in the slime.

Rumo sighed. ‘I was wondering if there’s any place more frightful than this one.’

Smyke had to think harder than usual before something occurred to him.

‘They say there is,’ he replied.

‘Worse than here? What’s it called?’

‘Netherworld,’ said Smyke.

‘Netherworld …’ Rumo repeated. It sounded sinister.

‘I don’t know if it’s an actual place or just a word. Perhaps it’s just a tall tale. I’ve often heard soldiers speak of it around their campfires. They say there’s another world beneath this one and it’s filled with evil, vicious creatures. Everyone has his own idea of the place, but I’ve never met anyone who has actually been there.’

‘Maybe it’s because no one who goes to evil places ever comes back.’

‘You’re in a grim mood today, my boy. How about a riddle?’

‘All right,’ said Rumo. ‘Ask me one.’

Smyke had taken to setting Rumo simple problems. It sharpened the youngster’s wits and dispelled his gloomy thoughts.

‘What can penetrate a wall but isn’t a nail?’ asked Smyke.

‘No idea,’ said Rumo.

‘I know, but I want you to work it out.’

And he sank back into his pool, because he couldn’t have endured any more questions that evening.

One afternoon the grille slid back with a crash and four Demonocles charged in, bellowing. Rumo had an uneasy feeling as the giants strode across the cave. They came straight for him, grabbed him by the arms and threw him into the empty cage from which they’d taken the lion. Then they locked the door of the cage and strode out. Rumo’s free-ranging days were over. He shook the bars and growled at the departing giants. The cage was cramped, which meant he would have to relieve himself where he slept. He too was now at the Demonocles’ mercy. He shook the bars again, but they were immovable and not even his teeth could bite through metal. How would Smyke explain his plan now? He couldn’t visit the pool any more and the Shark Grub had never left his slimy basin. Rumo had no idea if he was capable of doing so.

Smyke had dived to the bottom of his pool, where not even his dorsal fin showed above the surface. The big fat bubbles that rose from the depths burst with a revolting sound, pervading the cave with a noisome stench of sulphur.

Smyke was pondering. One aspect of his escape plan had still to be worked out. For this he needed certain information. He couldn’t quite put his finger on it, but he knew that he could refresh his powers of recall in the Chamber of Memories. Having excreted some extra big bubbles of slime, he set off through the convolutions of his brain in the slow, leisurely way that came naturally to him.

Then he entered the Chamber of Memories. Ignoring the draped picture as usual, he resolutely made for one he hadn’t looked at for a long time. It was a picture of a table: one of the red felt gaming tables to be found in all Fort Una’s gambling dens. The felt was littered with coloured wooden gaming chips, and as he looked at them he also heard the hum of voices, the whirr of roulette wheels and the rattle of dice – all the sounds that had once filled his days and nights. And then he was sitting at the table, his gaming table, which he ran in his capacity as an officially certified croupier and dealer. He wanted to remember one particular night – the night the mad professor had come to his table.

The professor with seven brains

‘Excuse me,’ said the peculiar little gnome, ‘but would you permit me to have a bit of a flutter?’

Being a croupier accustomed to people with far coarser manners, Smyke was amused by his courteous tone.

‘Of course,’ he replied. ‘How about a hand of rumo?’

‘Whatever you suggest,’ said the gnome and he took his place at the table. He was obviously a Nocturnomath, a Zamonian life form with several brains. Smyke had never seen one before, but the grotesque excrescences on the goggle-eyed, humpbacked creature’s head matched other people’s descriptions of the breed.

‘May I introduce myself? Nightingale’s the name – Professor Abdullah Nightingale.’

Smyke inclined his head. ‘Smyke – Volzotan Smyke. For a start, then, a hand of rumo.’ He dealt the cards.

The professor won every game they played: rumo, Midgardian rummy, Florinthian poker, Catch the Troll and, finally, rumo again. Before three hours were up a small fortune in coloured chips was piled high in front of him. He was clearly using a system based on the number seven – that much Smyke had gathered.

Nightingale placed his bets in stacks of seven chips on numbers divisible by seven, and he also played his cards according to a system somehow based on seven. He not only drew attention to this each time but explained his intricate calculations, which entailed the addition, multiplication and division of figures up to seven digits long, until Smyke’s brain was in turmoil. The Nocturnomath won again and again. He wasn’t there to make money, he declared, but to test a mathematical system.

The sweat that was streaming down Smyke’s face had nothing to do with the torrid atmosphere of the gambling den; it was the cold sweat of mortal fear. The table was surrounded by curious spectators, among them the owners of the saloon, two Vulpheads named Henko and Hasso van Drill. One-eyed twins and former highwaymen, Henko and Hasso had amassed their starting capital by strangling well-heeled travellers in the neighbourhood of Devil’s Gulch. It was their hard-earned money that was passing into the professor’s possession.

Although Fort Una’s gambling dens did not cheat their patrons outright, they were run on semi-criminal lines. This meant that the ultimate winners were the owners of the gambling dens, not their customers. To ensure that the system ran smoothly, the owners employed people like Smyke, professional card-sharks who could beat the average player without cheating. They sometimes let the gamblers win and even paid out substantial sums, but the house always made a decent profit by the end of the night. And now this professor was overturning the whole concept of Fort Una. He was winning every game without exception. That wasn’t just a run of luck; it was a breach of Fort Una’s unwritten law: Everyone loses in the end.

Smyke was powerless to prevent Nightingale from multiplying his winnings every time. If he went on this way the house would be bankrupt after a few more games. The Vulpheads gave Smyke a look that conveyed some idea of the treatment he could expect in the alley behind the saloon if he failed to end the professor’s lucky streak in a very short time.

‘How about another hand?’ the professor asked brightly as he arranged his chips in stacks of seven. ‘I’m developing quite a taste for gambling.’

‘As you wish,�

�� Smyke said in a choking voice. ‘With us, the customer is king.’

‘You ought to do something about that excessive perspiration of yours,’ the professor said, glancing at the film of sweat on Smyke’s brow. ‘Salt tablets work wonders sometimes.’

Smyke dealt the cards with an agonised smile. The professor mumbled some figures, staked his entire winnings on a single hand, played his cards in accordance with his absurd system of sevens – and won again.

‘My goodness.’ He chuckled as he raked in his winnings. ‘What am I to do with all this money? I shall probably invest it in darkness research, or possibly construct an oracular chest of drawers. The possibilities are limitless! Another hand?’

He won four more games, which almost cleaned out the Vulpheads. Smyke’s heart was pounding, his head spinning. He yearned to wring the mad professor’s scraggy, vulturine neck, but the Vulphead brothers would save him the trouble. Another mysterious accident in a lawless town: a fatal fall down the back steps of a gambling den sustained by an absent-minded, intoxicated professor whose clothes reeked of brandy. No one would give a damn. A doctor bribed by the Vulpheads would make out the death certificate (‘Accidental death, self-induced. Evidence of alcohol abuse.’) and there would be one more nameless grave in the desert behind Fort Una.

In despair, Smyke longed to inform the Nocturnomath that he was gambling with his own life as well as the dealer’s. The spectators and the Vulphead brothers pressed closer, listening expectantly to the polite conversation in progress between the dealer and the gambler.

‘I know,’ said a voice in Smyke’s head.

‘That’s great!’ he thought. ‘I’m so scared I’ve lost my wits. I’m starting to hear voices.’

‘You’re only hearing one voice and it’s mine. It’s me, Nightingale,’ said the voice. ‘Don’t give yourself away.’

Smyke tensed, staring across the table. The professor appeared to be engrossed in his hand.

‘Listen: I possess the gift of telepathy. No big deal for a Nocturnomath – we all have it. And now to your problem. I may seem a trifle unsophisticated, but I’m not tired of life. I’ve no intention of letting two notorious villains stab me to death in a dark alley, or something similar, for the sake of filthy lucre. However, I’d like to finish testing my system, savour my triumph to the full and leave these crooks to sweat a little longer. Shall we play another hand of rumo?’

Either it really was the professor’s voice he was hearing, or he’d gone mad after all – Smyke wasn’t sure. The Nocturnomath hadn’t favoured him with a single glance throughout his speech; in fact, he been joking with the gamblers and crooks standing around them. Mechanically, Smyke dealt the cards.

‘What, another hand?’ the professor said loudly. ‘I was going to call it a night, actually, but never mind. One more, then. All or nothing as before?’

The Vulphead brothers scowled and felt in their pockets to satisfy themselves that their Florinthian glass daggers were there.

‘All or nothing!’ the professor cried gaily. Everyone held their breath.

‘Er, 777,777,777.77 divided by 7,777,777.777 divided by 77 comes to, er, er …’ the professor muttered to himself, moving his cards around with maddening deliberation. Smyke’s rivulets of perspiration had combined to form an oily film that covered his entire body. He glistened like a waxed apple.

‘Professor?’ he called desperately in his head. ‘Professor? Surely you don’t intend to win again? That would be suicide. Suicide and murder, if you include me!’

But there was no reply.

‘Let’s see,’ muttered the Nocturnomath. ‘The square root of 777,777,777,777.7 divided by the product of 77,777,777.777 times 777 to the power of, er, 7, makes, er …’ The rest was unintelligible. The professor laid his cards down one by one. He had won yet again.

‘Professor?!’ If Smyke’s thoughts had been audible; that would have been an anguished cry.

Nightingale looked at him expressionlessly. ‘Where can I cash in my chips?’ he asked. ‘I hope you’ll provide me with some sacks to carry my winnings in.’

‘Of course,’ one of the Vulpheads said coolly. ‘We’ll settle up with you in our office, that’s the best plan. Over a couple of drinks on the house.’

Smyke’s head was spinning. He could already see himself lying sprawled in the alley, choking on his own blood.

‘Another hand?’ he cried desperately.

If anything had sealed his fate it was those words. The Vulpheads might otherwise have let him off with a few broken arms and a tongue-lashing, but now he had focused everyone’s attention on the professor once more – just when the brothers had almost persuaded him to accompany them to their office. That was tantamount to a self-imposed death sentence.

‘Another hand of rumo?’ said the professor. ‘Double or quits?’

Smyke nodded.

Nightingale grinned. ‘Why not?’

Smyke shuffled the cards again and dealt. Nightingale began to mumble figures to himself, and it was all the Vulpheads could do not to murder the professor and their croupier in front of everyone.

‘7,777,777.7 multiplied by 7 is, er …’ Nightingale glanced at the Vulpheads to see whether they were sweating too. They were.

Smyke made another half-hearted attempt at mental communication. ‘Professor?’ he telepathised. ‘Professor Nightingale?’

No response. Nightingale was tapping his cards, lost in thought.

‘7,777,777.7 multiplied by 7 to the power of 7 minus the square root of 777 makes, er …’

‘Professor!’ Smyke yelled in his head. ‘Are you there?’

Nothing. Not a sound, not a flicker of emotion on Nightingale’s face. So he really had succumbed to a hallucination engendered by his own panic.

‘777,777,777.777 multiplied by 77 divided by the sum of 7,777 plus 777,777 times 777 divided by 6 …’ burbled the professor.

Smyke gave a start. Divided by six? It was the first time Nightingale’s calculations had included any number apart from seven.

The Nocturnomath laid his cards down with an amiable smile. The spectators bent over the table. A groan ran round the saloon. The professor had lost.

‘Yes?’ said Nightingale’s voice in Smyke’s head. ‘You called me?’

Smyke didn’t reply, he was too busy raking in the professor’s chips and exchanging looks of relief with the Vulphead brothers, who could now let go of their glass daggers.

‘That was an interesting experience,’ the professor told Smyke in his normal voice as the crowd dispersed. ‘Easy come, easy go! It seems that the mathematical system capable of defeating chance has yet to be devised. At all events, mine will be consigned to the Chamber of Unperfected Patents. Self-criticism is the mother of invention.’

Smyke stared at him. ‘But you could have gone on winning for ever, you know that perfectly well.’

Nightingale rose and laid his hand on Smyke’s shoulder. ‘There’s only one thing that goes on for ever, and that’s darkness.’

At that moment something happened: the reason why Smyke had entered the Chamber of Memories and seen the picture of the gaming table. When the professor’s hand touched his shoulder a tidal wave of information surged through Smyke’s brain so swiftly and unexpectedly that it jolted his head and almost sent him toppling over backwards, complete with his chair.

Through that brief physical contact the absent-minded Nocturnomath had deliberately or inadvertently collated the ideas that were racing through his various brains and transmitted them to Smyke by means of his telepathic ability to infect others with intellectual bacteria – for Nightingale a quite commonplace process, for Smyke a memorable experience. Briefly summarised, those ideas related to seismographic oscillations in the Gloomberg Mountains; astronomical vortex physics (black holes, nebular motion, solar-system rotation); chemical communication between South Zamonian insects, reptiles and orchids (olfactory transmission of information, exchanges of fluid between garter snakes, pollen vibrati

on by nectar-producing Venus flytraps and the haptic ability of Zamonian honey bees to communicate with Zamonian flora); geodetic anomalies in the Demerara Desert and their influence on Zamonian travelogues; the connection between the alpenhorn music of Demon Range and the prevalence of avalanches in the same region; and the repercussions of nocturnomathic philosophysics on the pseudo-scientific writings of Hildegard Mythmaker. They also related to the Zebraskan glorification of obstinacy; to deposits of sea salt in algal dimensions; to the telepathic perception of multicerebral life forms when massively bombarded with scintillas and irradiated with will-o’-the-wisps; to the densification of darkness in the cerebral convolutions of persons artificially dispirited by being subjected to brass band music and low barometric pressure; and – the real reason why Smyke had activated this memory in the first place – to the abnormal structure of Demonocles’ tongues and its effects on their sense of balance.

Smyke had found the memory that would help him to perfect his escape plan.

Rumo’s special diet

Rumo grew at an even more breakneck pace in the next few weeks. He discovered some change in his body almost daily, whether it was a powerful muscle, a fully developed claw, an enlarged bone, or a brand-new tooth.

The Demonocles’ interest in him had steadily intensified since he’d been in the cage. He had previously been allotted the same fare as all the others: the scraps of fish and bone the Demonocles tossed into the cave, the indeterminate mush they tipped into troughs for the vegetarians among their captives, and the pools they continually replenished with rainwater. The Demonocles were not particularly intelligent, but they were not so stupid as to let their prisoners starve. In any case the food they gave them – millet, raw vegetables, gnawed bones and the like – was worthless to themselves from the culinary aspect because it could neither kick nor scream.

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

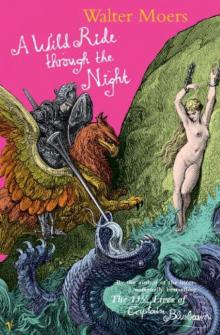

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night