- Home

- Walter Moers

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Part One - Dancelot’s Bequest

A Word of Warning

To Bookholm

Lindworm Castle

Dancelot’s Death

The Manuscript

The City of Dreaming Books

The Hotel from Hell

Kibitzer’s Warning

Colophonius Regenschein

Mulled Coffee and Bee-Bread

Out of the Frying Pan

Pfistomel Smyke’s Typographical Laboratory

Timber-Time

The Trombophone Concert

Book Rage

Four Hundred Frog Recipes

Smyke’s Inheritance

Part Two - The Catacombs of Bookholm

The Living Corpse

The Hazardous Books

The Sea and the Lighthouses

Unholm

The Kingdom of the Dead

The Twofold Spider

The Giant Skull

The Bloodstained Trail

Three Distinguished Writers

A Very Short Chapter in Which Precious Little Happens

The Leather Grotto

Orming

A Cyclopean Lullaby

The Chamber of Marvels

The Invisible Gateway

The Star of the Catacombs

One Breakfast and Two Confessions

Murch and Maggot

A Pike in a Shoal of Trout

The Apprentice Bookling

Zack hitti zopp

Bookholm’s Greatest Hero

The Book Machine

The Rusty Gnomes’ Bookway

The Song of the Harpyrs

A Shout and a Sigh

Denizens of the Darkness

The Symbols

Shadowhall Castle

The Hair-Raisers

The Melancholy Ghost

The Animatomes

Homuncolossus

The Shadow King’s Story

Exiled to Darkness

The Bookhunter Hunter

The Plan

Conversation with a Dead Man

The Inebriated Gorilla

Thirst

The Alphabet of the Stars

The Dancing Lesson

The Vocabulary Chamber

Theerio and Practice

In the Cellar

Dinosaur Sweat

The Giant’s Zoo

A Good Story

The Library of the Orm

Addicted

The Bargain

Farewell to Shadowhall

Back to the Leather Grotto

The Memorial

The Greatest Danger of All

The Fire Demons of Nether Florinth

The White Sheep of the Smyke Family

The Renegades

The Nightingalian Impossibility Key

The Beginning and the End

Out of Breath

The Shadow King Laughs

The Orm

ALSO BY WALTER MOERS

The 13½ Lives of Captain Bluebear

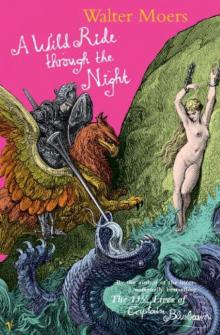

A Wild Ride Through the Night

Rumo

Published by Harvill Secker, 2006

Copyright © Piper Verlag GmbH, München 2004 Translation copyright © John Brownjohn, 2006

Walter Moers has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by HARVILL SECKER

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road London sw1v 2sa

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited 20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney, New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Limited 18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Random House South Africa (Pty) Limited Isle of Houghton, Corner of Boundary Road & Carse O’Gowrie, Houghton 2198, South Africa

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009 www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publication of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut

eISBN : 978-1-590-20368-2

Papers used by Random House are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests; the manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin

Typeset in Stempel Garamond by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex Printed and bound in Great Britain by William Clowes Ltd, Beccles, Suffolk

http://us.penguingroup.com

Part One

Dancelot’s Bequest

Optimus Yarnspinner

Where shadows dim with shadows mate

in caverns deep and dark,

where old books dream of bygone days

when they were wood and bark,

where diamonds from coal are born

and no birds ever sing,

that region is the dread domain

ruled by the Shadow King.

A Word of Warning

This is where my story begins. It tells how I came into possession of The Bloody Book and acquired the Orm. It’s not a story for people with thin skins and weak nerves, whom I would advise to replace this book on the pile at once and slink off to the children’s section. Shoo! Begone, you cry-babies and quaffers of camomile tea, you wimps and softies! This book tells of a place where reading is still a genuine adventure, and by adventure I mean the old-fashioned definition of the word that appears in the Zamonian Dictionary: ‘A daring enterprise undertaken in a spirit of curiosity or temerity, it is potentially life-threatening, harbours unforeseeable dangers and sometimes proves fatal.’

Yes, I speak of a place where reading can drive people insane. Where books may injure and poison them - indeed, even kill them. Only those who are thoroughly prepared to take such risks in order to read this book - only those willing to hazard their lives in so doing - should accompany me to the next paragraph. The remainder I congratulate on their wise but yellow-bellied decision to stay behind. Farewell, you cowards! I wish you a long and boring life, and, on that note, bid you goodbye!

So . . . Having probably reduced my readers to a tiny band of reckless souls at the very outset, I should like to bid the rest of you a hearty welcome. Greetings, my intrepid friends, you’re cut from the cloth of which true adventurers are made! Let us waste no more time and set out at once on our journey. For it is a journey on which we’re embarking, a journey to Bookholm, the City of Dreaming Books. Tie your shoelaces good and tight, because our route will take us first across a vast expanse of rugged, stony terrain, then across a monotonous stretch of prairie where the grass is dense, waist-high and razor-sharp, and finally - along gloomy, labyrinthine, perilous passages - deep into the bowels of the earth. I cannot predict how many of us will return. I can only urge you never to lose heart whatever befalls us.

And don’t say I didn’t warn you!

To Bookholm

In western Zamonia, when you’ve traversed the Dullsgard Plateau in an easterly direction and finally left its rippling expanses of grassland behind you, the skyline suddenly recedes in a dramatic way. You can look far, far out across the boundless plain to where, in the distance, it merges with the Demerara Desert. If the weather is fine and the atmosphere clear, you will be able to discern a speck amid the sparse vegetation of this arid wasteland. As you advance, so it will grow larger, take on jagged outlines, sprout gabled roofs and eventually reveal itself to be the legendary city that bears the name of Bookholm.

You can smell the place from a long way off. It reeks of old books. It’s as if you’ve opened the door of a gigantic second-hand bookshop - as if yo

u’ve stirred up a cloud of unadulterated book dust and blown the detritus from millions of mouldering volumes straight into your face. There are folk who dislike that smell and turn on their heel as soon as it assails their nostrils. It isn’t an agreeable odour, granted. Hopelessly antiquated, it is eloquent of decay and dissolution, mildew and mortality. But it also has other associations: a hint of acidity reminiscent of lemon trees in flower; the stimulating scent of old leather; the acrid, intelligent tang of printer’s ink; and, overlying all else, a reassuring aroma of wood.

I’m not talking about living wood or resinous forests and fresh pine needles; I mean felled, stripped, pulped, bleached, rolled and guillotined wood - in short, paper. Ah yes, my intellectually inquisitive friends, you too can smell it now, the odour of forgotten knowledge and age-old traditions of craftsmanship. Very well, let us quicken our pace! The odour grows stronger and more alluring, and the sight of those gabled houses more distinct with every step towards Bookholm we take. Hundreds, nay, thousands of slender chimneys project from the city’s roofs, darkening the sky with a pall of greasy smoke and compounding the odour of books with other scents: the aroma of freshly brewed coffee and fresh-baked bread, of charcoal-broiled meat studded with herbs. Again we redouble our rate of advance, and our burning desire to open a book becomes allied with the hankering for a cup of hot chocolate flavoured with cinnamon and a slice of pound cake warm from the oven. Faster! Faster!

We reach the city limits at last, weary, hungry, thirsty, curious - and a trifle disappointed. There are no impressive city walls, no well-guarded gates in the shape, perhaps, of a huge book that creaks open at our knock - no, just a few narrow streets by way of which Zamonian life forms of the most diverse kinds enter or leave the city. Most of them do so with stacks of books under their arms - indeed, many tow whole handcarts laden with reading matter behind them. Were it not for all those books, the cityscape would resemble any other.

So here we are, my dauntless companions - here on the magical outskirts of Bookholm. This is where the city has its highly unspectacular beginnings. Soon we shall cross its invisible threshold, enter its streets and explore its mysteries.

Soon.

But first I should like to pause for a moment and tell you why I came here at all. There’s a reason for every journey, and mine was prompted by boredom and the recklessness of youth, by a wish to break the bounds of my normal existence and familiarise myself with life and the world at large. I also wanted to keep a promise made to someone on his deathbed. Last but not least, I was on the track of a fascinating secret. But first things first, my friends!

Lindworm Castle

When a youthful inhabitant of Lindworm Castle1 becomes old enough to read, his parents assign him a so-called authorial godfather. The latter, who is usually some relation or close family friend, assumes responsibility for the young dinosaur’s literary education from that time on. The authorial godfather teaches his charge to read and write, introduces him to Zamonian literature and tutors him in the craft of authorship. He makes him recite poems, enriches his vocabulary and undertakes all the steps required to ensure his godchild’s artistic development.

My own authorial godfather was Dancelot Wordwright. A maternal uncle who might have been hewn from the primeval rock on which Lindworm Castle stands, he was over eight hundred years old when he became my sponsor. Uncle Dancelot was a workmanlike writer devoid of any exalted ambitions. He wrote to order, mainly eulogies for festive occasions, and was considered to be a talented composer of after-dinner speeches and funeral orations. More of a reader than an author and more of a connoisseur of literature than an originator thereof, he sat on countless juries, organised literary competitions, and was a freelance copy-editor and ghost-writer. He himself had written only one book, The Joys of Gardening, in which he expatiated in impressive language on the cultivation of cauliflowers and the philosophical implications of the compost heap. Almost as fond of his garden as he was of literature, Dancelot never tired of drawing comparisons between the taming of nature and the art of poetry. To him, a home-grown strawberry plant was the equal of an ode of his own composition, a row of asparagus comparable to a rhyming pattern and a compost heap to a philosophical essay. You must permit me, my long-suffering readers, to quote a brief passage from his book, which has long been out of print. Dancelot’s description of a common or garden blue cauliflower conveys a far more vivid impression of my authorial godfather than I could transmit in a thousand words:

The cultivation of the blue cauliflower is a rather remarkable process. What pays the price in this case is not the foliation, for a change, but the inflorescence. The gardener encourages the umbel’s temporary obesity. Crowded together into a compact head, its countless little buds swell, together with their stalks, into an amorphous mass of bluish vegetable fat. Thus, the cauliflower is a flower that has come to grief on its own obesity before flowering; or, to be more precise, a multiplicity of unsuccessful flowers, a degenerate panicled umbel. How in the world can such a bloated creature, with its plump and swollen ovaries, propagate itself? It, too, would return to nature after an excursion into the realm of the unnatural, but the gardener gives it no time to do so: he harvests the cauliflower at the zenith of its aberration, the highest and most palatable stage in its obesity, when the taste of this adipose plant approximates to that of a rissole. The seed collector, on the other hand, leaves the bulbous blue mass in its corner of the garden and permits it to revert to its better self. When he goes to look at it after three weeks, instead of three pounds of vegetable obesity, he finds a very loosely freely flowering bush with bees and flying beetles humming round it. The unnaturally swollen pale-blue stalks have converted their thickness into length and become fleshy stems tipped with a number of sparsely distributed yellow flowers. The few buds that have proved durable turn blue and swell up, then flower and produce seeds. Honest and true to nature, these gallant little survivors are the saviours of the cauliflower fraternity.

Yes, there you have Dancelot Wordwright as he lived and breathed: in tune with nature, in love with language, unfailingly accurate in his observations, optimistic, a trifle eccentric, and - where the subject of his literary labours, the cauliflower, was concerned - as tedious as could be.

All my memories of him are pleasant, discounting the three months that followed one of Lindworm Castle’s numerous sieges, during which a stone launched by a trebuchet struck him on the head and left him convinced that he was a cupboard full of dirty spectacles. Although I feared at the time that he would never re-emerge from his delirium, he did, in fact, recover from that severe blow on the head. Unfortunately, no such miraculous recovery occurred in the case of his final and fatal bout of influenza.

Dancelot’s Death

When Dancelot breathed his last at the conclusion of a long and fulfilled dinosaurian existence spanning eight hundred and eighty-eight years, I was a mere stripling of seventy-seven summers and had never once set foot outside Lindworm Castle. He died of a minor influenzal infection that proved too much for his weakened immune system (an occurrence which reinforced my fundamental doubts about the reliability of immune systems in general).

On that ill-starred day I sat beside his deathbed and noted down the dialogue that follows. My authorial godfather had requested me to record his last words in writing. Not because he had grown so conceited that he wished his moribund sighs to be preserved for posterity, but because he thought it would provide me with a unique opportunity to gather authentic material in this special field. He died, therefore, in the execution of his duty as an authorial godfather.

Dancelot: ‘I’m dying, my boy.’

I (inarticulately, fighting back my tears): ‘Huh . . .’

Dancelot: ‘I far from approve of death, either from fatalistic motives or with the philosophical resignation of old age, but I suppose I must come to terms with it. Each of us is granted only one cask and mine is tolerably full.’

(I’m glad in retrospect that he employed the ca

sk metaphor because it indicates that he regarded his life as rich and fulfilled. A person who looks back on his life and likens it to a brimming cask, not an empty bucket, has accomplished a great deal.)

Dancelot: ‘Listen, my boy. I have little enough to leave you, at least from the pecuniary aspect. That you already know. I have never become one of those opulent Lindworm Festival authors with sacks full of royalties piled high in their cellars. I intend to bequeath you my garden, although I know you aren’t too keen on vegetables.’

(This was true. As a young Lindworm I had little use for the glorification of cauliflowers and hymns to rhubarb in Dancelot’s treatise on gardening, and I made no secret of it. Dancelot’s seed germinated only in later years, when I had established a garden of my own, grew blue cauliflowers and derived much inspiration from the taming of nature.)

Dancelot: ‘I’m rather clammy at present . . .’

(I couldn’t help laughing, despite the depressing situation, because ‘clammy’ is Zamonian slang for ‘broke’, and there was something unintentionally amusing about his use of that word in his present sweaty state. Had I myself employed this ill-judged resort to black humour in an essay, Dancelot would probably have red-pencilled it. I managed to smother my guffaw in a handkerchief and pass it off as tearful nose-blowing.)

Dancelot: . . . so I can’t leave you anything from the material point of view.’

(I made a dismissive gesture and sobbed, this time with genuine emotion. Even at death’s door, he was concerned about my future. It was touching.)

Dancelot: But I do possess something worth considerably more than all the treasures in Zamonia. At least to an author.’

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night