- Home

- Walter Moers

The City of Dreaming Books Page 6

The City of Dreaming Books Read online

Page 6

Next, Regenschein became apprenticed to one of Bookholm’s ex-libris perfumers. This was a profession unique to the city. For hundreds of years, wealthy collectors had made a practice of impregnating their books with perfumes manufactured to order. This lent their treasures an olfactory stamp of ownership, an aromatic ex-libris that was not only detectable and unmistakable, even in the dark, but invaluable to anyone concealing his books beneath the surface.

Colophonius Regenschein was equipped with a good sense of smell. Although Vulpheads’ noses are not as sensitive as those of Wolpertings, or even of dogs, because their canine instincts and faculties have atrophied over the generations, they can nonetheless recognise olfactory nuances undetectable by other Zamonian life forms. Regenschein sniffed his way through the whole library of scents belonging to Olfactorio de Papyros, an ex-libris perfumer whose family business had helped to endow legendary collections and rare volumes with their unique fragrances for many generations. He memorised the books’ titles and their authors’ names, the details of where and when they had disappeared, and any other particulars about them he could find. He sniffed leather and paper, linen and pasteboard, and learnt how these different materials reacted to being steeped in lemon juice, rosewater and hundreds of other aromatic essences.

The Smoked Cookbooks published by the Saffron Press, the balm-scented manuscripts of the naturopath Dr Greenfinger, the Pine-Needle Pamphlets of the Foliar Period, Prince Zaan of Florinth’s autobiography (rubbed with almond kernels), the Rickshaw Demons’ Curry Book, the ethereal library of mad Prince Oggnagogg - Colophonius Regenschein became acquainted with every book perfume ever made. He learnt that books could smell of soil, snow, tomatoes, seaweed, fish, cinnamon, honey, wet fur, dried grass and charred wood, and he also learnt how these odours could change over the centuries, mingling with the aromas of the catacombs to such an extent that they often underwent a complete transformation.

In addition to this, of course, Regenschein studied Zamonian literature. He read everything that came his way, whether novel, poem or essay, play script, biography or collection of letters. He became a walking encyclopaedia. Every last corner of his memory was crammed with texts and particulars relating to Zamonian creative writing and the life and works of the most varied authors.

Colophonius Regenschein trained his body as well as his mind. He developed a breathing technique that enabled him to survive even in the most airless conditions. He also went on a slimming diet that reduced his weight sufficiently for him to squeeze through the narrowest of passages and fissures in the rock. In the end, when he felt thoroughly qualified to embark on a career as a Bookhunter, he decided to do so with a bang that would be heard all over Bookholm.

He did not choose any old bookshop for his first excursion, nor did he set off on an aimless quest. No, he turned his expedition into a venture that evoked scornful accusations of megalomania from everyone in the city. Through the medium of the Live Newspapers he announced exactly when and where he would descend into the catacombs and when and where he would reappear on the surface. He also gave advance notice of the three books he intended to unearth:

Princess Daintyhoof, the only surviving signed first edition of Hermo Phink’s legendary account of how the Wolpertings originated, bound in Nurn leaves;

Treatise on Cannibalism, an account of the customs and conventions of mad Prince Oggnagogg’s Cadaverous Cannibals by Orlog Goo, who was devoured by his objects of study on completing the book; and

The Twelve Thousand Precepts, the Bookemists’ abstruse list of rules, possibly the most scandalous book in the whole of Zamonia.

Regenschein’s announcement was somewhat presumptuous, given that the three books in question had for many years been regarded as lost and stood high on the Golden List, so even one of them would have made its discoverer wealthy. Last but not least, Regenschein further announced - doubtless so as to render his venture more spectacular still - that he would publicly commit suicide if he failed to bring the above-named works to the surface within a week.

Everyone in Bookholm agreed that the Vulphead had lost his wits. It was thought absolutely impossible to do what no other Bookhunter had succeeded in doing over the years, namely, to snaffle three Golden List books at once, let alone to do so within the space of a single week.

Amid roars of sarcastic laughter from a large crowd of spectators, the audacious Vulphead descended into the catacombs of Bookholm at the appointed hour. Bets were laid against his chances of success as the week went by. On the predicted day a vast crowd assembled round the bookshop from which he proposed to emerge after regaining the surface. Just before noon Colophonius Regenschein staggered out of the main entrance and into the street. Sodden from head to foot with blood, he had an iron arrow protruding from his right shoulder and was carrying three books under his arm: Princess Daintyhoof, Treatise on Cannibalism and The Twelve Thousand Precepts. He smiled, waved to the marvelling crowd - and collapsed unconscious.

In the next chapter of his book Regenschein described in every detail how he had planned this expedition, made long-term preparations for it and finally carried it out. He had begun by combining numerous descriptions of various parts of the catacombs into a complete mental picture of their layout. Then he assembled all the facts he had learnt while studying the three books he was after. He knew exactly when they had been printed, who had printed them and the addresses of the bookshops that had taken delivery of the first editions. Next, he traced their subsequent history with the aid of documentary records. He discovered that part of the first printing had been destroyed by a big fire, that some salvaged copies had been sold to another bookshop, that unsaleable stocks had been pulped, that individual copies had survived, and so on and so forth. He knew from diaries, letters and publishers’ financial accounts how well or badly the books had sold and why, and where they had been consigned to the rubbish dump. The same sources yielded other useful items of information, for instance that a copy of the first edition of Princess Daintyhoof had turned up in the window of a certain bookshop, that it had eventually fetched an immense sum at auction and that it had disappeared after the purchaser had been robbed on the way home. Regenschein discovered that the putative thief, a celebrated book pirate whose sobriquet was Gory Hands, had been walled up alive by a fellow criminal named Blorr the Bricklayer. While examining the latter’s papers, he further discovered a map on which Blorr had marked all the places where he had stored his victims complete with their possessions.

Once in the catacombs, Colophonius Regenschein was greatly assisted by his study of Zamonian literary history and book printing. He could classify every author and literary school, knew which antiquarian booksellers devoted themselves to certain writers or specialised fields, and could determine from a book’s binding and the condition of its spine which edition it belonged to, when this had been published and how many copies had been printed. Regenschein had no need to ferret systematically through each stack of volumes like other Bookhunters. Armed with his jellyfish lamp, he had only to hurry along the passages glancing swiftly to left and right. He even derived valuable information from the order in which various subterranean collections had been stored and this guided him to the treasures he was seeking.

His apprenticeship with the ex-libris perfumer now paid off. One sniff sufficed to tell him that a whole roomful of books had once belonged to a collector who had imbued all his volumes with the aroma of freshly brewed coffee. Regenschein could tell for sure that the copy of Princess Daintyhoof he sought was not among them because it had belonged to an eccentric with such an insane love of cats that he impregnated his entire collection with the unpleasant odour of feline urine. A less proficient Bookhunter would now have gone sniffing for this everywhere, but Regenschein knew that the olfactory components of cat’s piss took on the unique and penetrating smell of rotting seaweed after a century at most underground. When he was at last confronted by a time-worn brick wall in the depths of the catacombs and detected a smell o

f the sea, he knew that he had found his first book.

Where The Twelve Thousand Precepts was concerned, Regenschein’s study of literary history had acquainted him with the year in which it had been banned and burnt by the Atlantean vice squad. As always in such cases, one copy had been ceremoniously conveyed into the catacombs and walled up there. Discovered by Bookhunters a century later, it changed hands several times before being destroyed by a bookshop fire - or so the authorities claimed. Regenschein, who had scoured the municipal records for that year, came across a bankruptcy petition lodged by the dealer who had owned the relevant bookshop. Further research in Bookholm’s municipal library had enabled him to unearth the diary of the dealer’s wife, in which she confessed that her husband had torched the shop himself and hidden his most valuable books in the catacombs. Having helped him to make away with them, she was able to give a precise description of their whereabouts.

Regenschein found the Treatise on Cannibalism by employing a similar process of detection. However, dear readers, I will spare you a full account of this and confine myself to saying that it entailed a detailed knowledge of paper manufacture in ancient times, of the microscopic technique required to cast lead type for footnotes, of the decline of Ornian isosyllabism during Zamonia’s Singing Wars and the preservation of goatskin covers by means of linseed oil.

In short, Colophonius Regenschein found the books he was after even before the appointed week had elapsed, or within three days, so he had to stick it out in the catacombs for the remaining four in order to meet his self-imposed deadline exactly.

When he finally made for the surface he was attacked by another Bookhunter. As I already mentioned, the only professional qualification Regenschein lacked was the criminal initiative possessed by his colleagues. He simply hadn’t considered the possibility that someone might try to rob him of his haul.

That someone was Rongkong Koma, Bookholm’s most notorious and dangerous Bookhunter, an evil individual who owed all his successes to the fact that he never went looking for rare books himself but stole them from others on principle. Having learnt of Regenschein’s grandiloquent announcement, he lay in wait beneath the bookshop from which his prospective victim was due to emerge. That was all he had to do apart from spearing Regenschein in the back with an iron javelin.

Fortunately for Regenschein, Rongkong Koma missed his heart and merely pierced his shoulder. A ferocious duel ensued. Although unarmed, Regenschein managed to inflict so many wounds on Koma with his canine teeth that the rapacious Bookhunter lost a great deal of blood and took to his heels, but not without swearing eternal enmity.

The Vulphead only just made it to the surface before passing out and did not regain consciousness for a week. He had lived up to his ambitious predictions, however, and the Live Newspapers were quick to spread the word. Overnight, Colophonius Regenschein had become the most famous Bookhunter of all.

He could also have become the best-paid Bookhunter of all, because collectors and dealers bombarded him with offers. But Regenschein turned them all down. Although he resumed bookhunting when he had recuperated - this time armed and forever on his guard against Rongkong Koma - he kept most of the books he acquired for himself. His ultimate intention soon became clear: Colophonius Regenschein aimed to collect one copy of every last book on the Golden List. He managed to do this in an incredibly short space of time and he also returned to the surface laden with other books which, although not on the list, were valuable in the extreme. These he sold, using the proceeds to purchase one of the handsomest old buildings in Bookholm, where he set up the Library of the Golden List as a place in which rare works could be studied under supervision for scholarly purposes. Colophonius Regenschein thus became Bookholm’s greatest hero: a combination of adventurer, patron and paragon.

Despite his wealth and fame, however, and although his expeditions became ever more hazardous, Regenschein could not resist the lure of the catacombs. He was as hated down there as he was popular in the world above. Some of the most brutal Bookhunters dogged his footsteps and tried to steal his finds. They included Nassim Ghandari, nicknamed ‘The Noose’ because he crept up behind his victims and garrotted them with cheese wire; Imran the Invisible, so called because he was thin enough to be mistaken in the dark for a pit prop - until you were suddenly transfixed by a poisoned arrow from his blowpipe; Reverberus Echo, whose talent for vocal and acoustic mimicry led his victims astray and lured them into death traps, after which he cannibalised them to cover his tracks; and Lembo ‘The Snake’ Chekhani, a Bookhunter who had sunk so low, morally speaking, that he wriggled along on his belly camouflaged in manuscripts, as supple and attenuated as his nickname implied. Tarik Tabari, Hunk Hoggno, Erman de Griswold, Hadwin Paxi, Azlif Khesmu, Horgul the Hairless, ‘Blondie’ Snotsniff, the Toto Twins - Colophonius Regenschein became involuntarily acquainted with all of these Bookhunters and several more besides, but none of them managed to rob him of a single book and most sustained severe injuries in the course of their encounters with him. Some abandoned the profession and others steered well clear of him in the future. Only one repeatedly and deliberately challenged his supremacy: Rongkong Koma the Terrible. The most fearsome of all Bookhunters lay in wait for Regenschein again and again, doggedly thirsting for revenge, and the two of them fought almost a dozen strenuous duels from which neither emerged a clear winner, usually because they broke off hostilities by reason of exhaustion. One such confrontation mentioned by Regenschein was a crossbow duel after which, riddled with poisoned arrows, he just managed to reach the safety of the bookshop owned by Ahmed ben Kibitzer, who nursed him back to health. I’m sure, dear readers, that you can imagine how astonished I was, while reading Regenschein’s book, to come across the name of the crotchety little Nocturnomath who had tried to send me packing.

But Bookhunters weren’t the only danger that lurked beneath Bookholm. No one had ever descended as far into the catacombs as Colophonius Regenschein, and no one had set eyes on as many of its marvels and monstrosities. He wrote of miles-deep caverns filled with millions of ancient volumes in the process of being devoured by phosphorescent worms and moths. He wrote of tunnels infested with blind and transparent insects that hunted anything within reach of their yards-long antennae; of frightful winged creatures - he called them Harpyrs - whose frightful screams had almost robbed him of his sanity on one occasion; of the Rusty Gnomes’ Bookway, an immense subterranean railroad system said to have been constructed thousands of years ago by a dwarfish race of very skilful craftsmen. He also told of Unholm, the catacombs’ gigantic rubbish dump, where millions of books lay mouldering away.

Regenschein firmly believed in the existence of the Fearsome Booklings, a race of one-eyed creatures dwelling deep in the bowels of Bookholm and reputed to devour (alive) anything that came their way. He even entertained no doubts about the popular myth of a race of giants said to have lived in the deepest and biggest of all the subterranean caverns, where they stoked Zamonia’s volcanoes. He had seen so many incredible sights in the catacombs that he regarded nothing, absolutely nothing, as being beyond the bounds of possibility.

Although his book had been accused of transgressing the frontier between truth and fiction, it did so in such a subtle way that I didn’t care which page I was on. Regenschein’s writing utterly enthralled me. I devoured chapter after chapter as Bookholm’s nightlife raged around me, pausing only occasionally to signal for another pot of coffee before avidly reading on. Alas, dear readers, I cannot possibly summarise all the details Regenschein disclosed about the world beneath my feet, there were simply too many of them.

I will, however, make mention of one chapter, for it was in that one, the last of all, that Regenschein’s book really took off. It was devoted to the Shadow King.

The story of the Shadow King was one of the more recent legends - only a few score years old - about the Bookholmian underworld. It told of the birth of a being said to have established a reign of terror in the catacombs far surpassing any

of the Bookhunters’ atrocities. The legend went as follows:

Many shadows exist in the gloom of the catacombs. Shadows of living creatures, of dead things, of vermin that creep, crawl and fly, of Bookhunters, of stalagmites and stalactites. A multifarious race of silhouettes dancing restlessly over the tunnel roofs and book-lined walls, they strike terror into many intruders or drive them insane. One day in the not too distant past, so legend had it, these incorporeal beings grew tired of their anarchic living conditions and elected a leader. They superimposed one shadow, one silhouette, one shade of darkness on another until all these became amalgamated into a demicreature. Half alive and half dead, half solid and half insubstantial, half visible and half invisible, he became their ruler and spiritual executor. In other words, the Shadow King.

This was only the popular version of the legend, for there were several different theories about who or what the Shadow King really was. Bookhunters claimed he was the wrathful spirit of the Dreaming Books, their incarnate anger at having been forgotten and buried in the catacombs. They believed that this spirit had come to wreak revenge on all living creatures, and that he dwelt in a subterranean abode named Shadowhall Castle. Such was the Bookhunters’ version.

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

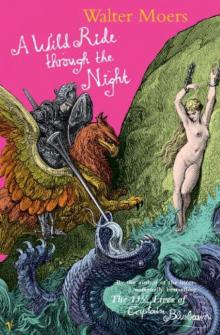

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night