- Home

- Walter Moers

The Alchemaster's Apprentice: A Novel Page 6

The Alchemaster's Apprentice: A Novel Read online

Page 6

Then, with a contented grunt, he stretched out on the moss for a brief digestive siesta. As he contemplated the pigeon’s pale skeleton with a meditative eye and rolled it playfully to and fro with his paws, his mood darkened. It horrified him to think of the trouble Ghoolion was taking to fatten him up. The Alchemaster had actually hauled a bathtub all the way up here, possibly at the risk of his own life. He had embedded it in the moss and filled it with bucket after bucket of milk. He had not only roasted that delicious pigeon but obtained the dolls’ clothes and fashioned the little boats. How deadly serious he must be, and how eager to see his victim’s scrawny frame put on weight! Echo sprang to his feet, suddenly wide awake again.

Feeling uneasy and shivering a little, he climbed still higher. It was quite impossible to explore the roof systematically. The stairways would sometimes lead upwards or downwards for no apparent reason, then turn a corner and end abruptly in a sloping expanse of tiles. When that happened there was nothing for it but to retrace one’s steps or scale the precipitous slope. Echo occasionally peered in through the triangular window embrasures that gaped everywhere, but all he could see was total darkness. Were the Leathermice in there, or was there another loft beneath this confounded roof, the real loft that shielded the vampires from wind and weather? Now and then he came across strange carved ornaments, bizarre stone sculptures and grotesque gargoyles. He felt like an explorer discovering the ruins of a vanished civilisation.

There! Yet another appetising aroma in the air! Fried sausages? Fishcakes? Grilled chicken? In search of its source, Echo stole round a corner and came upon another spot where Ghoolion had created an artificial paradise for Crats. Protruding from a smallish, flattish expanse of roof was a tall red brick chimney, which the Alchemaster had transformed into a travesty of a Christmas tree with the aid of florist’s wire and sprigs of fir. Suspended from them on thin strings were some rib-tickling titbits: crisp-skinned fried sausages, dainty little fishcakes, lamb cutlets scented with garlic, breaded chicken drumsticks and crispy wings. Beneath them stood a pot of fresh, sweetened cream.

Echo inhaled deeply. His dark thoughts promptly evaporated, his mouth started watering. He proceeded to knock the little snacks off the ‘tree’ with his paw and devour them. Far from as simple and unsophisticated as it had seemed at first sight, the cuisine displayed definite expertise. The sausages were stuffed with tiny shrimps, chopped onions and grated apple, and seasoned with sage; the drumsticks had clearly been marinated for days in red wine, with the result that their pale-pink meat dissolved on the tongue like butter. The lamb cutlets had been wrapped in raw ham, studded with rosemary and then fried. Everything tasted superb.

‘Well?’ a voice said suddenly. ‘Enjoying it?’

Echo was so startled that the lamb cutlet he was eating fell out of his mouth. He looked left and right but couldn’t see a soul.

‘Up here!’ called the voice.

Echo looked up at the chimney. Poking out of it was the head of a Cyclopean Tuwituwu, which was staring at him with its single piercing eye.

‘I asked if you were enjoying it.’ The Tuwituwu had a deep, resonant voice. ‘I sope ho, anyway.’

Sope ho? Had the bird said ‘sope ho’?

‘Many thanks,’ Echo replied cautiously. ‘Yes, I am. Is this your food I’ve been eating?’

‘Oh, no,’ said the Tuwituwu, ‘I never touch the stuff, I just live here. The chimney is my desirence.’

‘I didn’t realise anyone lived up there.’

‘Well, now you know. But keep it to yourself, I wouldn’t like it pade mublic. Permit me to indrotuce myself. My name is Theodore T. Theodore, but you may call me Theo.’

Echo didn’t venture to ask what the T between the two Theodores stood for. Theodore, perhaps.

‘Delighted to meet you,’ he said. ‘My name is Echo. You really live in this chimney?’

‘Yes, it’s never used. It has a little roof of its own, that’s good enough for me.’ The Tuwituwu stared at Echo in silence. ‘If you can conummicate with me,’ it said at length, ‘you must be a Crat.’

‘That’s right,’ Echo replied, ‘I am.’

‘You’ve got two livers, did you know that? I’m something of an expert on gioloby.’

‘Biology, you mean.’

Theodore behaved as if he hadn’t heard.

‘It would scafinate me to know how you got past the Meatherlice,’ he went on. ‘You’re the first creature to set foot on this roof that didn’t wossess pings.’

Scafinate? Wossess pings? Echo was becoming more and more puzzled by Theodore’s speech patterns. ‘I simply talked to them,’ he replied.

‘Ah, the art of genotiation,’ said Theodore. ‘I understand now. You’re a born miplodat.’

Echo caught on at last: Theodore obviously had a problem with words. Or a broplem, as he would have put it.

‘I’d sooner use my brains than my claws.’

‘So you conummicated with them instead of fighting. You’re a facipist!’ Theodore exclaimed. ‘That’s splendid - we couldn’t be more alike in our views. Any disagreement can be resolved by dational riscussion.’

‘You know a lot of long words,’ said Echo.

‘You can say that again,’ Theodore replied, fluffing out his chest a little. ‘I’m a molypath, a walking endyclocepia, an autorithy of the first order. However, I’m not interested showing off my uniserval brilliance, just in guinlistic precision. You don’t need to have gone to uniservity for that. Personal itiniative is enough.’

‘Are you another of Ghoolion’s tenants?’

‘I’ll ignore that question! I’ve nothing to do with that crinimal invididual! I occupied this chimney in tropest against Ghoolion’s evil chaminations.’

‘You aren’t too fond of him, then?’

‘I’m not the only one, either! He’s a despot, a social rapasite. He infects and tancominates the whole town. As long as he continues to modinate it the inhabitants will never be free. What we need is a relovution! A relovution of the trolepariat of Lamaisea!’

Echo involuntarily glanced around to see if anyone was listening.

‘Aren’t you being a little rash, sounding off like this?’ he asked in a low voice. ‘I mean, I’m a total stranger, and you -’

‘No, no, not a stranger,’ the Tuwituwu broke in soothingly, ‘I know all about you. You’re a victim of Ghoolion’s almechistic aspirations. He plans to slaughter you and fat you of your strip.’

‘How did you know?’

‘In the first place, because he does that to all kinds of creatures except Meatherlice. I know everything - everything! I’ve had this building under vurseillance for many years. I know every chimney, every pecret sassage. I’ve seen the animals in their cages. I’ve seen him reduce them to falls of bat. Now, only the cages are left.’

‘You creep around inside the chimneys?’ said Echo. ‘Why?’

‘To keep an eye on Ghoolion and his doings. I’m everywhere and nowhere. Nobody sees me, but I see everything. I’ve eavesdropped on many of Ghoolion’s molitary sonologues. I know his ambitious plans, his tatolitarian dreams.’

‘Isn’t that rather risky?’ asked Echo. ‘I mean, if he caught you …’

Theodore ignored this question too. He leant over, opened his one eye wide, and whispered: ‘Listen, my friend. You’re in great danger. Ghoolion aims to be the creator of life and master of death, no less. Megalomaniacal though it sounds, he’s on the verge of filfulling that ambition and you’re the last little mog in his cachine.’

‘How do you know that?’

The Tuwituwu fluffed out his chest again.

‘Just an above-average pacacity for working things out, perhaps, or a flair for tedection, or a stininctive feeling. Call it initution, if you like. There have lately been many incidations that an acopalyptic miclax, a sidaster of uncepredented gamnitude, is in the offing! And things have speeded up since your arrival. Ghoolion has never been so cheerful. You should have seen him at his exme

ripents last night. He was in the heventh seaven!’

Echo was becoming suspicious. How could he be sure that this bizarre bird was telling the truth? Perhaps it was a confederate of Ghoolion’s under orders to test him.

‘Why are you telling me all this?’

‘Because you’re the only one who can stop him,’ the Tuwituwu whispered.

‘Meaning what?’

‘For some siconderable time now, the Master Almechist has been skimming off and preserving the fat of rare animals - their olfactory soul, so to speak. He blends these fats and fragrances again and again in the lebief that this will produce a masic baterial from which he can create new life. I lebieve him to be so close to that goal that he hopes to attain it at the next full moon. All he needs is the fat and the soul of one last animal: a Crat, as your presence here implies. The way I see it, you’re the last meraining emelent in his master plan. Your fat is the one missing indegrient. Only you can put the bikosh on the whole idea.’

‘Really?’ said Echo. ‘How, exactly?’

‘It’s quite simple: run away. Bill your felly for a few days, then disappear into the blue. Deprive him of your Crat fat and you’ll hash his dopes completely.’

‘But we’ve got a contract.’

‘A cantroct?’ The Tuwituwu stared at Echo in horror. ‘A legal codument? Really? That’s bad.’

‘Yes,’ sighed Echo, ‘and contracts have to be kept.’

‘Nonsense, cantrocts are made to be broken! But a cantroct with Ghoolion … That’s another matter.’

‘What do you mean?’

Now it was the bird’s turn to look around apprehensively.

‘Ghoolion has ways of enforcing your cantroct with him.’

‘What ways are you talking about?’

‘You’ll soon find out if you try to break it.’

‘That’s more or less what the Leathermice told me. So you also believe I’ve no hope of getting out of here alive?’

‘I didn’t say that. I’m potimistic by nature, but yours is an expectionally rare case. I shall have to give it a little more thought.’

The foliage of the artificial Christmas tree rustled in a sudden gust of wind. Echo looked round. Some big fat storm clouds in the distance were drawing nearer.

‘The clamitic conditions are about to undergo a drastic fortransmation, ’ said the Tuwituwu. ‘The otmasphere is charged with electricity, the beromatric pressure is falling - that means a stunderthorm. Cindotions up here will become pretty unpleasant. I shall retire to my cellar to catch a mouse or two. I still have to ornagise my own meals, alas.’

‘Why not help yourself to some of these sausages?’ Echo said invitingly.

The Tuwituwu looked indignant.

‘Absolutely not! I never touch anything that comes from Ghoolion’s biadolical kitchen. It’s an iron-cast principle of mine.’

‘Suit yourself,’ said Echo, ‘but you don’t know what you’re missing.’

‘You’d better find yourself a nice dry spot somewhere,’ said Theodore.

‘I will. Many thanks for the conversation and the good advice.’

‘That wasn’t a conservation, it was a cansporitorial get-together. I didn’t advise you, either, I simply made some stragetic suggestions. From now on we’re a team.’

‘A team?’

‘An alliance forged by fate. We’re brothers in spirit, camrodes-in-arms. See you again soon.’

Theodore T. Theodore shut his single eye and disappeared slowly down the chimney.

Echo turned and scanned the heavens. Big-bellied rain clouds were towering over the Blue Mountains and the moist, warm wind was steadily increasing in strength. He was beginning to feel uneasy out there on the roof; being at the mercy of a thunderstorm really didn’t appeal to him. Theodore’s topsy-turvy utterances had left him bemused. Besides, he was sleepy after gorging himself, so he resolved to go inside and have a little nap to help him digest what he’d heard and eaten. It had been a thoroughly eventful morning.

The Cooked Ghost

Echo could hardly believe he’d managed to give Ghoolion the slip. Flatly ignoring the terms of their contract, he had sneaked out of the castle, scampered all the way across Malaisea and left the outskirts of the town behind him for the first time in his life. He’d been afraid that the Alchemaster would lay him low with a remote-controlled thunderbolt or turn him to stone, but nothing of the kind occurred. Now he was up in the mountains he’d seen from the roof of Ghoolion’s castle. Walls of blue rock towered on either side of him, far higher than the walls flanking Malaisea’s narrow streets - higher, even, than the Alchemaster’s castle.

Suddenly he heard a clatter all round him. The rock faces rang with the tramp of marching feet and the rattle of bones. Echo knew at once what was making this din: Ghoolion’s iron-soled boots were beating out their menacing rhythm. The sound was accompanied by an asphyxiating stench of sulphur and phosphorus. Then the whole mountain range grew dark as if a sudden storm had gathered overhead. Echo looked up, fearing the worst, and there, taller even than the very mountains, stood Ghoolion. Dressed all in black, he had grown into a giant a thousand times bigger than before. He bent down and, with a casual backhander, knocked off a mountain peak. It exploded into countless fragments as it fell, and an irresistible avalanche of rock came rumbling down the mountainside in Echo’s direction. He tried to run, but his legs felt so leaden he could hardly detach his paws from the ground. The thunderous avalanche drew nearer and nearer, the first rocks hurtled past him. And then, looking more closely, he saw to his horror that they weren’t rocks at all: they were human heads, each of them adorned with Ghoolion’s face. ‘Irrevocably committed!’ one of them shouted. ‘Indissolubly binding!’ yelled the next. ‘Legally enforceable!’ cried another.

Echo woke up. He was lying in his basket beside Ghoolion’s stove - lying in a thoroughly unnatural position with the blanket wound as tightly round his legs as ropes around a captive. He must have been wrestling with its imprisoning folds in his sleep. Grunting and groaning, he extricated himself and climbed sleepily, laboriously, out of his basket.

The thunderstorm was raging immediately above the castle as Echo stole along the passage to Ghoolion’s laboratory. Rain came slanting in through the empty window embrasures, lightning lit up the passage so brightly at times that the little Crat had to shut his eyes. ‘Windowpanes,’ he muttered, ducking his head. ‘Windowpanes would be a good thing right now.’

Ghoolion had been expecting him. He was taking advantage of the dramatic meteorological conditions to perform a spectacular alchemical experiment for Echo’s benefit. What better place to stage it than his laboratory, with rain-laden storm clouds billowing past its tall, pointed windows? What better background music than the menacing rumble of thunder nearby? Distributed around the room were dozens of Anguish Candles whose fitful light and subdued groans added to the indispensably ominous atmosphere.

The Alchemaster was wearing a wine-red velvet cloak with gold appliqués and a tricorn hat of pitch-black ravens’ feathers, which made him look more diabolical than ever. He was standing beside his cauldron. A good fire was burning beneath it, as usual, but no exotic animal was being rendered down on this occasion. The cauldron’s bubbling, seething contents appeared to be plain water.

‘Well,’ asked Ghoolion, ‘how did you get on with the Leathermice? Was breakfast on the roof to your satisfaction?’

‘I can’t complain,’ Echo replied. ‘The roof is fabulous, but the Leathermice take a bit of getting used to.’ He studiously avoided mentioning his encounter with Theodore T. Theodore.

‘Good. I think you’ve already gained a pound or two.’

The clouds emitted a deafening peal of thunder. Echo gave a jump. He had learnt to respect thunderstorms since being evicted from his former home. It wasn’t childish timidity that made him start at every thunderclap and every flash of lightning, it was the thoroughly justified fear that something catastrophic might happen. He had seen shafts

of lightning split whole oak trees in two and set barns ablaze. The laboratory was situated at a great height, rain clouds were swirling through its open windows, and its bristling array of silver, copper and iron instruments presented a perfect target for electrical discharges. The room was so full of combustible and explosive materials and powders that a single thunderbolt would have sufficed to send the whole castle sky-high, yet the Alchemaster was proceeding with his work as calmly as if he relished the dangers of the situation - in fact, Echo half suspected that he was secretly masterminding the storm.

‘Listen carefully,’ Ghoolion said as he worked on the fire beneath the cauldron with a pair of bellows. ‘I’m going to teach you a few basic facts about alchemy.’

‘A few basic facts?’ Echo replied with a touch of disappointment. ‘“Secrets which even the most experienced alchemist would give his eye teeth to know” - that was what you said!’

‘You can’t measure the universe without learning your two-times table first,’ Ghoolion retorted over a clap of thunder. ‘You can’t write a novel without mastering the alphabet or compose a symphony without being able to read a score. How can I tell you about Prima Zateria if you don’t even know how to cook a ghost?’

Echo pricked up his ears. ‘Is that what we’re going to do, cook a ghost?’

‘Possibly, we’ll see. Maybe, maybe not. It doesn’t work every time. Alchemy is a science, but not, alas, an exact one. It’s as close to an art as any science can be and not every work of art succeeds.’

Echo’s curiosity was aroused. Coming closer, he wound round Ghoolion’s legs.

‘Actually,’ Ghoolion went on, ‘this isn’t a work of art. It’s just a trick, a kind of joke.’

‘I thought you didn’t make jokes.’

‘Who says so?’ Ghoolion looked down at the Crat in surprise.

‘You did.’

‘I did? Really? The things one says without thinking … I’ve always been fond of jokes.’

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

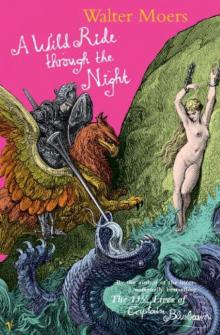

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night