- Home

- Walter Moers

The City of Dreaming Books Page 12

The City of Dreaming Books Read online

Page 12

Finally, Ilfo held up a bottle. ‘This, my friends,’ he announced triumphantly, ‘is the last remaining bottle of Comet Wine, the finest and most delicious, rarest and most valuable wine in Zamonia. I’ve no need to house and tend any more bottles and barrels, no need to pay any more taxes and wages, nor will I need to go in fear of the Zamonian customs and excise authorities. All I shall need is this one bottle of wine, which is now worth a fortune, and all I shall have to do is watch it appreciate in value every day. I’m retiring.’

‘What about us? What’s to become of us?’ asked one of his minions.

Ilfo Guzzard eyed him sympathetically.

‘You?’ he said. ‘What’s to become of you? You’ll be unemployed, of course. I’m firing you all as of now.’

Not until that moment, as he stood there in the midst of hundreds of unemployed workers with history’s most valuable bottle of wine in his hand, did it dawn on Ilfo Guzzard that it might have been wiser to give them notice of dismissal in writing. Their eyes were blazing with murderous intent - and also with a desire to own that priceless bottle of wine. They slowly and steadily converged on him.

‘Very well,’ thought Ilfo, who may have been a rotten employer but was certainly no coward, ‘if I must die, at least I’ll die drunk. No one’s going to own my Comet Wine but me.’

He knocked the top off the bottle and drained it at a gulp. Then he was lynched by his workers. But he had underestimated the greed his speech had kindled in them. Having carried his corpse to the biggest wine press on the estate, they threw him into it and juiced him. They squeezed Ilfo until the last drop of Comet Wine had been extracted from his corpse, along with his blood, and bottled the frightful liquid in a jeroboam. It was now indeed the rarest and most valuable wine in Zamonia.

But the truly horrific story of Comet Wine was only just beginning, because it brought its successive owners nothing but the worst of bad luck.

Ilfo Guzzard’s workers were executed for his murder, the next owner of the bottle was struck by a meteor and the one after that devoured by ants while asleep. Wherever the bottle went, murder and mayhem, war and madness soon followed. Many people believed that Comet Wine could restore the dead to life, so it was greatly coveted in alchemistic circles. The jeroboam passed from hand to hand, leaving a trail of bloodshed throughout Zamonia, until one day the trail suddenly ended and the receptacle containing Ilfo Guzzard’s wine and blood seemed to vanish from the face of the earth.

The musical epilogue was a quivering tremolo that embodied the full horror of the story. Absolute silence followed.

I awoke from a state akin to hypnosis. The concertgoers around me were murmuring excitedly, the trombophonists bottle-brushing their mouthpieces with a satisfied air.

‘That was new,’ exclaimed the dwarf beside me. ‘The Comet Wine piece wasn’t on last week’s programme.’

Aha, so they didn’t always perform the same pieces. I felt privileged to have been present at a kind of première and closer in spirit to the admirers of Murkholmian trombophone music. By now, ten Midgard Serpents wouldn’t have dragged me from my seat. I was eager for more of the same.

The murmurs died away, the musicians raised their instruments once more.

‘Next comes some gruesic, I reckon,’ the dwarf said with obvious pleasure. ‘It’ll go well with that gory tale of the Comet Wine.’

‘What’s gruesic?’ I enquired.

‘Wait and see,’ the dwarf replied mysteriously. ‘Now things will get really weird.’ He broke off in mid chuckle. ‘Hey, didn’t you bring a shawl? You’ll catch your death.’

I couldn’t have cared less. I was willing to make any sacrifice for the sake of some more trombophone music.

Several of the Murkholmers projected shimmering notes high into the night sky while others blew discreetly in the bass register. I shut my eyes again, but this time I saw no overwhelming panorama. Instead, my head became filled with a profound understanding of the Dervish music of Late Medieval Zamonia - of which I’d known absolutely nothing until then.

Dervish music, I suddenly knew for certain, was based on a heptametrical scale whose intervals were measured in units called shrooti. Two shrooti equalled a semitone, four shrooti a whole tone and twenty-two shrooti an octave. That an interval should have taken its name from a musician was an honour unique in Zamonian musical history. Octavius Shrooti, the legendary Dervish composer of the Late Middle Ages, had evolved a gruesome form of music, or ‘gruesic’, capable of being blended with any composition. It was based on sounds calculated to inspire dread: dogs howling in the night, creaking hinges, the cry of a screech owl, anonymous voices whispering in the dark, rumbles from beneath the cellar stairs, malevolent titters in the attic, women weeping on a blasted heath, screams from a lunatic asylum, fingernails scratching slate - whatever made a person’s hair stand on end and could be imitated by musical instruments. Shrooti blended this gruesic with popular contemporary music in an extraordinarily successful manner. In his day people went to concerts mainly for the purpose of being scared out of their wits. Ovations took the form of cries of horror, mass fainting fits equated to requests for encores, and when panic-stricken members of the public jostled their way to the exit, screaming, the concert had been a complete success. Coiffeurs styled their clients’ hair so that it stood on end, chewed fingernails were considered chic, and concertgoers who chanced to meet in the street would greet each other with an affected ‘Eeek!’ and throw up their hands in simulated horror. A whole series of musical instruments originated at this time, among them the gallows harp, the devil’s bagpipes, the trembolo, the ten-valved macabrophone, the death saw, the dungeonica and the throttleflute. Not for nothing was Octavius Shrooti’s heyday known as the Gruesome Period.

The music died away and I opened my eyes. The dwarf beside me grinned.

‘Now you know: that was gruesic. But this is when it really hots up. Be prepared for anything!’ He sat back and closed his eyes with a sigh of anticipation.

Four trombophonists produced a chorus of howls that put me in mind of bloodhounds drowning in a castle moat. Two more imitated the bleating laughter with which Mountain Demons unleash avalanches. The fattest trombophonist seated in the middle of the orchestra persuaded his instrument to emit a despairing sigh like the final exhalation of someone being strangled by a garrotte. I also seemed to hear the pitiful cries of people buried alive and the screams of Ugglies burning to death.

Somewhat perturbed, I shut my eyes again. What horrific scenes would this music summon up in my mind? What terrible story would it recount?

At first I saw nothing but books. I was looking down an endless passage lined with shelves and old books. Surely nothing untoward could happen in an antiquarian bookshop? I studied the backs of the books more closely. Heavens, they weren’t just old, they were very old - so ancient, in fact, that I couldn’t decipher the titles. Several curious ceiling lights dispensed a ghostly, pulsating glow. Something was moving inside them. Were these the jellyfish lamps described by Regenschein?

At last I caught on: these were the catacombs of Bookholm - the labyrinth beneath the city, and I was in the midst of it! How fantastic, a subterranean journey into that mysterious, perilous world devoid of any personal risk! I need only listen to the music and devote myself to the scenes as they unfolded.

I opened my eyes briefly and closed them again, then repeated the procedure several times in succession. Sure enough, I could effortlessly alternate between the Municipal Gardens and the catacombs. Eyes open: Municipal Gardens. Eyes shut: catacombs.

Gardens.

Catacombs.

Gardens.

Catacombs.

Gardens.

Catacombs.

In the end I kept my eyes closed. Although I was actually seated on an uncomfortable folding chair in Bookholm’s Municipal Gardens, I was stealing along a dimly lit, book-lined passage far below ground. Amazing, what this trombophone music was capable of. Everything looked so real, too!

There was an overpowering smell of old paper - incredibly enough, I could even smell this scene! Not all the jellyfish ceiling lights were working properly - the creatures imprisoned in them shed a fitful glow - and some of the glass containers had cracked, releasing their occupants from captivity. A few of the phosphorescent invertebrates had clung to the shelves while escaping, whereas others had fallen to the floor and dried up.

What a weird place! There was a ubiquitous crackling noise, probably made by bookworms munching their way through paper. I could hear rats squeaking, beetles scuttling around and, overlying every other sound, a kind of whisper. I suddenly became aware that I could no longer hear any trombophone music.

I tried to open my eyes and catch a reassuring glimpse of the Municipal Gardens, but it was no use, my eyelids might just as well have been sewn shut. I could distinctly see the ominous scene in the catacombs, though. What a strange state of affairs, being able to see with my eyes shut! It no longer gave me a pleasurable thrill. My sole emotion was stark terror.

I tried to calm down by persuading myself that this was just another variation, a new and exciting addition to the concert programme. Now I was in the midst of the story - indeed, I might even be its principal character. But what kind of story was it and who exactly was I?

I stole further along the passage, looking nervously to right and left, up and down and back again. And then I was suddenly overcome by a strange sensation: I could smell which books were on the shelves. I had no need to waste time examining them, I could detect the lemony scent of the long-lost collection belonging to Prince Agoo Gaaz the Well-Read, not that his library held any present interest for me because - it abruptly dawned on me whose skin and story I now occupied - I was Colophonius Regenschein the Bookhunter!

How incredible! No, on the contrary, it was all too believable - it was frighteningly true! I had lost my ability to distinguish between dream and reality. I had become another person so completely that I was thinking his thoughts and sensing his fear. Now I knew why those precious volumes held no interest for me. I, Regenschein, was not alone in this labyrinth. I, Regenschein, was trying to escape from someone. I, Regenschein, had ceased to be the hunter and become the quarry: I was being hunted by the Shadow King.

I could hear him rustling and panting behind the books, and I sometimes fancied I could feel his hot breath on my neck, his sharp claws grazing my back. I made another desperate attempt to open my eyes, but in vain. I was imprisoned in Regenschein’s body, held captive in the catacombs of Bookholm.

Was it possible to die in an imaginary scenario? In a dream? What if Regenschein were killed? Was this still a story or the real thing? I could no longer tell. I knew only that I could feel Regenschein’s exhaustion in every limb - feel his aching muscles and burning lungs, his wildly beating heart. Then the passage ended abruptly and I was confronted by a wall of paper. My path was barred from floor to ceiling by a stack of manuscripts piled up at random. It was a dead end.

Feverishly, I debated what to do, retrace my steps and blunder into the arms of the Shadow King or try to demolish the wall of paper? I decided on the latter course of action and was about to set to work when the manuscripts began to stir. Nobody moved them - they moved of their own accord, slithering over each other like serpents, rustling as they crumpled up, straightened out again and eventually assumed the shape of a figure, a figure so horrific in appearance that -

‘Eeeeeeeeee!’

Someone was shrieking at the top of his voice.

‘Eeeeeeeeee!’

Was that Regenschein screaming in mortal terror?

‘Eeeeeeeeee!’

No, it was I, Optimus Yarnspinner, the cowardly lizard, who had flung himself to the ground and was begging for mercy.

‘Please!’ I entreated, sobbing. ‘Please spare me! I don’t want to die!’

‘You can open your eyes,’ said a voice, ‘the music has stopped.’

I opened my eyes. I was lying face down on the grass, just in front of my chair, with the dwarf and several other concertgoers bending over me.

‘Is he a tourist?’ asked someone.

‘Looks like a visitor from Lindworm Castle,’ said someone else.

It was really embarrassing. I scrambled to my feet, brushed the grass from my cloak and sat down again. The entire audience was staring at me. I could sense the eyes of Kibitzer and the Uggly boring into me. Even the musicians were looking my way.

‘They were bound to enjoy your discomfiture,’ the dwarf whispered sympathetically, ‘but you aren’t the first by any means. It’s a very intense experience, living out Colophonius Regenschein’s last few minutes in person.’

‘That’s one way of putting it,’ I whispered back, trying to sit as low in my chair as possible. I naturally couldn’t help being repelled by the notion that I’d screamed and whimpered and rolled around on the ground - for how long, I wondered? - so I was overjoyed when the Murkholmers raised their instruments and reclaimed everyone’s attention.

It sounded almost as if they were checking their valves again. One or another trombophonist blew a single note, seemingly at random, but that was all. Was the concert over? Was this a ritual of some kind? Even more gingerly and apprehensively than before, I experimented by shutting my eyes.

The image I saw this time was rather abstract. No landscape, no figures, no passages, just luminous little specks of various colours - yellow, red, blue - arranged in a circle. They lit up one after another, slowly at first, then at steadily decreasing intervals. The notes didn’t fit together or produce a harmonious melody. Yellow, red, blue, yellow, red, blue - the sequence continued without a break, round and round. It was the first time trombophone music had infused me with no emotion of any kind, neither euphoria nor fear. No story began to unfold.

‘The Optometric Rondo!’ gasped the dwarf beside me. ‘They’re going to play some Moomievillean Ophthalmic Polyphony.’

I knew this too, strangely enough, even though I had never before heard of Moomievillean Ophthalmic Polyphony. Yes, I was suddenly an expert on this esoteric branch of music and knew everything about it - for instance, that Moomievillean oculists had developed a diagnostic technique in which the interior of the eye was examined with a kaleidoscopic crystal of the kind found in the Impic Alps. In order to view every corner of the eye through the pupil, the oculist instructed the patient which way to look: straight up, up and to the right, right of centre, down and to the right, straight down, down and to the left, and so on until the eye had described a complete circle. Moomievillean oculists were Moomies, of course, and Moomies, as everyone knows, have six ears capable of picking up frequencies only spiders can detect. Their brains immediately convert all they hear into music, which is why they hum to themselves the whole time - as, of course, do Moomievillean oculists while at work. This is how it came about that one of them, a certain Dr Doremius Fasolati, noticed that the circular motion of the pupil, in conjunction with his musical humming, had a soothing effect on his patients. It even induced a slightly ecstatic sensation, with the result that - however shattering his diagnosis had been - they left his consulting room in a cheerful, almost euphoric frame of mind. This led to Fasolati’s invention of Ophthalmic Polyphony, a circular arrangement of notes in which the musical theme always returns to its starting point and begins all over again. So much for my new-found knowledge of Moomievillean Ophthalmic Polyphony.

‘The Optometric Rondo!’ shouted the audience. ‘Play the Optometric Rondo!’

I opened my eyes and saw the Murkholmian trombophonists rising to their feet. Shrill cries of enthusiasm rang out on all sides. I shut my eyes again.

Each note was now played by three trombophonists at the same time, which rendered it far louder and more piercing. The light this occasioned was brighter than before and the sound waves made my body vibrate. As one triplicated note followed another, the lights began to rotate. My vision, hearing and thoughts had also begun to revolve ever faster. Yellow-yellow-yellow, red-red-red, blue-

blue-blue . . . I saw a whirling trinity of colours, a flaming rainbow that contracted into a circle and went spinning through the darkness of outer space. Discarding all my doubts, I abandoned myself entirely to the rapture those abstract notes induced in me. We had entered a realm far transcending that of literary music - one in which stories and images, persons and their destinies had ceased to be important. All that I had heard hitherto seemed a mere preliminary to what I was now experiencing, whose immensity was such that I can summarise it in only three words: I became music.

I began by evaporating. Steam must experience that sensation when it escapes from boiling liquid and rises into the cooling air. For the first time in my life I felt free, truly free from all mundane constraints, disburdened of my body and liberated from my own thoughts.

Then I became sound, and anyone transmuted into sound becomes a wave. Indeed, I venture to say that anyone who knows what it’s like to become a sound wave is well on the way to fathoming the mysteries of the universe. I now understood the secret of music and knew what makes it so infinitely superior to all the other arts: its incorporeality. Once it has left an instrument it becomes its own master, a free and independent creature of sound, weightless, incorporeal and perfectly in tune with the universe.

That was how I felt: like music dancing with a flaming circle high above all else. Somewhere down below lay the world, my body, my cares and concerns, but they all seemed quite insignificant now. Here was the fiery wheel whose presence alone mattered. On and on it spun until its multicoloured luminosity seemed to flow into its interior as well, in three curving trajectories that united at its central point.

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

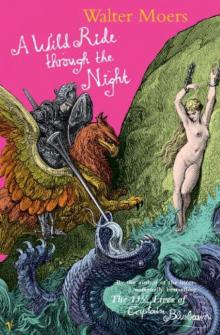

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night