- Home

- Walter Moers

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear Page 9

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear Read online

Page 9

* * *

Impic Alps, so far away,

listen to my sad refrain!

Will there ever come a day

when I see you all again?

* * *

Or:

* * *

Blue must my beloved be,

blue as billows in the sea,

blue as bluebirds on the wing,

blue as sapphires in a ring.

Yellow? Thank you very much!

Green I wouldn’t even touch.

As for red, it leaves me cold,

but I’ll love Bluebear till I’m old.

* * *

The dinosaurs

I preserve an especially vivid memory of the lesson in which Professor Nightingale portrayed the gradual emergence of life on our planet, from the unicellular organism to the highest life forms in existence.

He began by personifying a void, curling up into a ball and asserting in a faint, almost inaudible voice that he wasn’t there. This one could well believe, he looked so small and inconspicuous at that moment – indeed, had he told us he genuinely wasn’t there, we should probably have gone looking for him in the passage outside. Then he started to develop, at first into a cell, a tiny, sinuous creature that nervously wriggled through the warm primeval seas. Shoulders twitching, Nightingale imitated a cell lurching through the prehistoric ocean until, by degrees, he calmed down and transformed himself into a jellyfish. He inflated his body, extended both arms, rotated very slowly on his own axis, and seemed to be sinking, elegant as an open sun umbrella, into the depths. Next he became transmuted into a primeval fish, a predator equipped with huge jaws and projecting teeth. In search of prey, Nightingale dived under the desks and actually vanished for a while before suddenly rising to the surface with his eyes rolling wildly – a sight that frightened Qwerty almost to death.

Thereafter he blew out his cheeks and turned into a plump toad. This waddled along on dry land, croaking loudly, until it abruptly transformed itself into a huge, vicious, hissing alligator. Nightingale himself was so pleased with this performance that he slithered across the classroom on his belly a couple of times, teeth bared, and snapped at our ankles until we all climbed on our desks, squealing in terror. Highly delighted by this little joke, he proceeded to turn into a dinosaur.

To begin with he portrayed a leisurely herbivore, the huge but harmless brontosaurus. He lumbered ponderously to and fro, extended his long neck, and browsed on the pot of geraniums on his desk. To our amusement, he plucked a few of the flowers with his lips and munched them with relish. Eventually – and this sight has etched itself into my memory for ever – he presented an impressively authentic personification of Tyrannosaurus Rex, the most dangerous carnivorous predator of its day.

Getting up off all fours and standing erect, he peered around the classroom, ran his tongue over his teeth in a slow, sinister fashion, and scratched himself behind the ear with one little claw-tipped foreleg. Then he raised his head, screwed up his big, round, scientist’s eyes into narrow, menacing slits, and sniffed the air in all directions.

We all suddenly felt like dinosaur food.

Nightingale, or rather, the Tyrannosaurus Nightingalius, threw back its head and let out an ear-splitting roar. It was the most frightening sound I’d ever heard, the bellow of the Gourmetica insularis included. Fredda leapt from her chair, jumped on to my back, and clung there, trembling. Qwerty adopted a defensive stance, to the extent that a gelatinous creature from the 2364th Dimension can stand up at all. I myself prepared to bid the world farewell.

The dinosaur turned its head back and forth as if unable to decide which of us to devour first. Then, with lizardlike gait, it slowly waddled towards us. I could have sworn the ground shook with every step it took. Saliva dripped from its jaws, and I felt quite sure that this time Professor Nightingale had lost his reason – that each of his seven brains had malfunctioned simultaneously, and that he would act out his Tyrannosaurus Rex role to the bitter, bloody end. We had all crawled under my desk and were clinging to each other in terror. Saliva dripped on to the classroom floor as the Tyrannosaurus bent over us with parted lips and treated us to its craftiest grin. Then it suddenly stopped short and looked up as if it could hear an alarming sound in the distance. With a grunt of surprise, it took a crumpled piece of paper from the desk and tossed it into the air. The ball of paper landed on its head. As if fatally injured, it staggered dramatically towards us, let out another spine-chilling roar, and finally collapsed only inches away. The professor had just demonstrated what caused the dinosaurs to become extinct: a shower of enormous meteorites.

‘Once the dinosaurs had disappeared,’ Professor Nightingale’s lecture concluded, ‘there was really only one more interesting stage in the development of life.’ He spread his arms wide and grinned.

‘It’s right here in front of you: A Nocturnomath – the zenith of Creation.’

We were given no homework, no classroom projects, no marks, no oral tests. Nightingale asked no questions, never checked our state of knowledge, and never urged us to pay attention. He simply spoke and we listened.

Asking questions was completely taboo. Nightingale alone decided what subjects to tackle and when, what syllabus to study, or when it was time to move on to something else. He was like a radio whose knobs were being twiddled by a madman. He jumped from molecular biology to petrology, from petrology to ancient Egyptian architecture, from that to the study of putrescent gases on other planets, and from that to entomology with a detour that embraced the portrayal of the three-winged Zamonian bee in Atlantic encaustic paintings of the 14th century. We were taught what mattered most about Florinthian cheese sculptures, the caryatid culture of the sacred buildings of Grailsund, the therapeutic properties of the Peruvian ratanhia root, the mating dance of the Midgard Serpent, the leading lights of Zamonian speleology (of whom Nightingale was one), and the 250 principles governing the Aphavillean Declaration of Independence – all in a single afternoon.

Our spare time

Between classes we loitered in the gloomy tunnels or killed time in our bleak, windowless rooms. Occasionally we ventured out on to the ledge in front of the entrance to the Nocturnal Academy, where Mac had dropped me. We never lingered, however, because conditions at that altitude were extremely cold and windy even in summer. We simply stood there drawing in deep draughts of air until we developed hallucinations. Once we had satisfied our need for oxygen we retired to the gloomy maze of tunnels. We took no physical exercise, which Professor Nightingale thought absolutely pointless. He held that all forms of sport killed off essential brain cells. ‘Every overdeveloped muscle has a major intellectual achievement on its conscience,’ was his considered opinion.

There were no forms of entertainment, no games or books or anything else that might have distracted our attention from the professor’s lessons. When one lesson ended he would promptly retire to the darkroom to pursue his darkness experiments while we hung around, ate canned sardines, or dozed until he emerged and embarked on the next. Lessons were our only source of interest in the Gloombergs. That, no doubt, was another reason why Professor Nightingale had chosen to establish his Nocturnal Academy there.

The 2364th Dimension

I whiled away many an afternoon by persuading Qwerty to tell me about the 2364th Dimension. He didn’t like to do so because it aggravated his homesickness, but once he started there was no stopping him.

For some reason, there were a lot of carpets in his native dimension. One might even say that it consisted almost entirely of carpets, any gaps between them being occupied as a rule by dimensional hiatuses. In the 2364th Dimension a carpet denoted safety and stability; miss one, and you went hurtling into space. This was why carpet-weaving was the art that enjoyed the highest local esteem. Great efforts were made to turn every inhabitant of 2364 (as I must call Qwerty’s homeland for want of a proper name) into an efficient carpet-weaver. All other activities were held to be forms of idleness. Try as he genuinely

did to convey some idea of 2364’s carpets, even Qwerty found it impossible to describe their manifold patterns and weaves, shapes and colours, sizes and materials.

Wall-to-wall carpeting was frowned on, of course. Although there were broadloom carpets of vast dimensions, they never ran right up to the walls because there weren’t any walls in 2364. Qwerty told me of lovingly hand-woven runners made of pure gold thread, and of others consisting of several layers of cobwebs for durability’s sake. The inhabitants of 2364 had raised the art of weaving and knotting to a level that defies our comprehension. They could produce a carpet out of any conceivable material. According to Qwerty, 2364 boasted carpets made of glass, wood, sheet metal, and marble – even tea.

Everything was expressed in carpet form. Qwerty reported enthusiastically that poems and whole novels and epics were woven on looms, as were newspapers for adults and long, coloured runners with plenty of pictures and not much text for children. Very small, wafer-thin rugs served as banknotes, and for transportation the inhabitants used flying carpets of medium size or the larger carpet buses for which bus stops were installed throughout the 2364th Dimension.

For entertainment purposes one visited the carpet museum. Displayed there were carpets from bygone eras made of obsolete materials and bearing mysterious inscriptions in the runes of long extinct languages – ancient specimens rendered so threadbare by years of constant use that one could look through them into space. Contemporary artists vied with one another in devising new shapes and colours. There were circular and triangular carpets, star-shaped and corrugated ones, incredibly wide ones and some whose pile was so deep you had to fight your way through it like someone wading through a field of wheat.

In addition, every inhabitant of 2364 wove an autobiographical carpet, a sort of diary, retirement home and shroud all in one. All the memories, information, scenes and events people deemed important were woven into their carpet as time went by. Their latter years, during which it became steadily more dangerous to walk on other people’s carpets, they spent largely on their own, passing the time by looking at the scenes and memories they had recorded. When they died they were rolled up in their carpet and thrown down a dimensional hiatus. Personally, in view of all their efforts to avoid these pitfalls during their lifetime, I found this a rather barbaric practice.

As for Qwerty, it greatly saddened him that he no longer possessed an autobiographical carpet of his own.

Canned sardines

Meals at the Nocturnal Academy were as follows. Professor Nightingale never ate at all, or so it was said (he was rumoured to live on darkness). For everyone else – discounting Qwerty – there were canned sardines. Since Professor Nightingale attached no importance to food, he wasn’t too concerned about his pupils’ diet. ‘I don’t care what they eat as long as it’s always the same thing,’ was his motto.

Foodstuffs appealed to him only if they were very long-lasting, easy to prepare, extremely filling, and sold in stackable containers. Canned sardines perfectly fulfilled those requirements. The Nocturnal Academy’s pupils made a virtue of necessity and devised the most ingenious ways of preparing them. There was nothing to wash them down with except pure spring water, which came straight from the rock.

We were set no homework or exams, as I have already said, and there was nothing that might have assured Professor Nightingale that we were listening to him at all, let alone retaining what we heard. Even so, I had the feeling that I was becoming steadily brainier, and I could tell that the others were too.

The thing was, we’d taken to discussing and, if possible, cracking problems after school which the professor had only broached in class and left unresolved. Our standard of conversation rose day by day. Having begun by working out simple sums or correcting our spelling mistakes, we compiled our own logarithmic tables and deciphered some early Zamonian hieroglyphs unaided. After a few months we tackled the doctrines of Manu Kantimel, the founder of Grailsundian Demonism, and not only disproved them all but demonstrated that he had based them on an 11th-century message-in-a-bottle from Yhôll.

Whenever Fredda wasn’t actually clinging to my back and inserting writing implements in my facial orifices (she had recently started on my nostrils), we sat in the dining room and wrangled over Hackonian xenoplexy or the fluctuations of elf-wing atoms when exposed to magnetism.

A philosophical debate

One discussion between Fredda, Qwerty and myself ran more or less as follows:

I: ‘I’m just working on the foundations of South Zamonian Yobbism.’

Qwerty: ‘Oh, you mean the philosophical school of thought which assumes that no one object implies the existence of any other provided they’re viewed with the requisite insensitivity?’

I: ‘Precisely.’

Qwerty: ‘A most interesting intellectual approach. I infer from it that experience is the sum of ignorance plus militant stupidity.’

Fredda:

* * *

I entirely disagree. That’s far too crude a theory for my taste – it’s what happens when barbarians devote themselves to philosophy. The founder of Yobbism grew up in a swamp and hits his critics on the head with a club, everyone knows that. Let’s talk about astronomy instead. I’ve lately come to the conclusion that the universe isn’t expanding at all. But it isn’t contracting, either. It’s simply vacillating.

* * *

Qwerty: ‘Are you talking about a self-contained model of the world with the curvature symbol k = +1, in which phases of expansion and contraction periodically alternate?’

I: ‘Now that’s too crude for my taste!’

And so it went on …

A sound education

I became incredibly well-read, although there wasn’t a single book in the whole academy. In one of his lectures Professor Nightingale made a passing reference to The Cyclopean Crown, the epic poem by Wilfred the Wordsmith. Within a few hours I could recite it from start to finish, word for word, knew the forename of every early Zamonian deity, and could have turned out some flawless hexameters of my own. Nightingale also said something about Yohan Zafritter’s The Black Whale, a 4000-page novel describing the hunt for a Tyrannomobyus Rex, and before long I had not only memorized the entire text but knew how attach a line to a harpoon and coil it round a bollard in the stern. I also knew what ‘whale’ was in Latin, Greek, Icelandic, Polynesian, and Yhôllian, to wit, cetus, κητοζ, hvalur, piki-nui-nui, and trôm.

At the risk of being suspected of bragging, I was a walking encyclopedia of general knowledge. I had mastered all the languages in the known world, both dead and in current use, including all the Zamonian dialects – and they alone numbered over 20,000.

I knew whole sonnets of Zamonian baroque poetry by heart, was an expert on Atlantean air-painting, Dullsgardian minnesinging, and the analysis of comets’ tails. I could calculate the hourly expansion of the universe by observing the oscillations of the Gloomberg algal cell, replace a dislodged auditory ossicle with pincers, determine the blood group of a fossil insect by means of ommateal diagnosis, and gauge the number of animalcules in a glass of water from their weight – with my eyes shut. Grailsund Library, Zamonia’s largest collection of specialized works on demonology, did not list as many titles in its inventory as I myself carried in my head. Although I detested mathematics, the squaring of circles, the cubing of ellipses and the solving of problems of all kinds were child’s play to me.

My knowledge was far from confined to literature, the sciences, philosophy, and art. I was also versed in every conceivable sphere of daily life. I knew how to repair a church clock and cut a camshaft, how to calculate the statics of a dam, trepan a skull and construct a time bomb, how to put up a solid bell frame and clear a blocked toilet, how to tune a cello and palpate a liver. I could draw the ground plan of a cathedral, conduct a symphony orchestra, and calculate the trajectory of a cannon ball in a crosswind. I could, in no time at all, have fashioned an elegant lady’s shoe out of a piece of untanned leather and a stout thatch

ed roof out of reeds. I knew how to grind a lens and brew tasty wheat beer. I knew the names of every star in the sky and every micro-organism in the ocean.

Fredda’s farewell

The one thing I didn’t know was the source of all this knowledge. Then came the day when Fredda left us and was sent out into the world, her schooldays having ended. I should really have been relieved to be rid of such a pest, but I wasn’t. Fredda was my first love, after all, even if she was only an ugly Alpine Imp and our relationship was pretty one-sided. I’d grown accustomed to her, that’s all, and she was simply irreplaceable when it came to bringing our intellectual flights of fancy down to earth. I failed to understand how Nightingale could be heartless enough to kick her out, for that was just what he did. Alpine Imps have a congenital inability to cry, fortunately, or she would doubtless have kicked up a terrible fuss.

Her leavetaking was an extremely subdued occasion. Fredda was given no party, no diploma or school-leaver’s certificate. She simply said goodbye to us all (to me with a hoarse croak and an overly wet kiss) and was then conducted by Professor Nightingale to a fork in the tunnel. With a last sad wave in my direction, she hesitantly disappeared through the Nocturnal Academy’s official exit, which was rumoured by its pupils to lead into the labyrinth of passages that threaded the interior of the Gloomberg Mountains.

On returning to the classroom we found Fredda’s desk occupied by a newcomer, a timid unicorn named Flowergrazer.

Flowergrazer

Flowergrazer was as unlike Fredda as anyone could possibly imagine. A quiet, attentive pupil, he spoke in a low, inaudible voice and was boring in the extreme. He devoted his spare time to writing poems, all of which dealt with unicorns who were lonely, deeply distressed by their solitude, and called Flowergrazer.

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

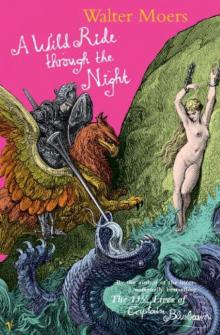

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night