- Home

- Walter Moers

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures Page 25

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures Read online

Page 25

Two dreams and a riddle

Rumo had two pet fantasies with which he lulled himself to sleep at night, turn and turn about. In one he was Prince Sangfroid rescuing Princess Rala from the clutches of an ever-changing succession of monsters or villains. In the other he was Wolperting’s new fencing champion, who deposed the legendary but ageing Ushan DeLucca in a breathtaking duel – watched by Rala and the entire fencing class, needless to say. Just as his dreams on Roaming Rock had constantly rehearsed the two phases of Smyke’s plan, so he now pictured himself repaying Ushan in the same coin for that humiliating nick on the nose. Having first played the fool and launched some clumsy attacks to put the fencing master off his guard, he would then surpass himself in a furious display of swordsmanship, taking his opponent apart until all that remained of him was a whimpering wretch who begged Rumo to take over his teaching post.

The vengeful thoughts Rumo entertained towards Ushan DeLucca differed in character from those he had felt for the Demonocles. He would exact a bloodless form of retribution that disarmed and humiliated his opponent with swordsmanlike finesse. Volzotan Smyke would have approved of this second dream.

Smyke … Rumo wondered what had become of his corpulent teacher. He would undoubtedly have found Wolperting to his taste had he been permitted to enter the city – a city where combat training was part of the school syllabus. He would also have made an excellent addition to the school staff: main subject strategy, subsidiary subject Zamonian military history. Rumo missed Smyke, but he wasn’t unduly worried about him. Anyone who had survived Roaming Rock could cope with any situation.

Rumo yawned. Then he remembered Smyke’s farewell riddle: What grows shorter and shorter the longer it gets? A candle? No, a burning candle simply gets shorter and shorter, not longer. Was the answer something visible? Maybe, maybe not. Still pondering this utterly insoluble riddle, Rumo drifted gently off to sleep.

Smyke very soon regretted his decision to part company with Rumo. He berated himself for being an utter fool. Having yielded to a spontaneous whim and dispensed with the amenities of Rumo’s companionship, he would now have to forage for food, light fires and cook for himself. As for the other advantages conferred by the presence of a battle-hardened Wolperting, he dreaded to think of them. He had gambled with destiny yet again, but his temperament was such that he quickly accepted his lot.

In the next few days he tried to convince himself how wonderful it was not to be hustled along by Rumo – to be able to take a breather whenever he felt like one. He spent several cold and almost sleepless nights because he failed to get a decent fire going and was deterred from shutting his eyes by sinister noises in the surrounding forest.

He was not unnaturally exhausted when, after a week, he met up with a convoy of Midgardian dwarfs, itinerant workers who toured the vineyards and helped with the grape harvest. It required all Smyke’s powers of persuasion to induce them to give him a ride on one of their donkey carts. Although unconvinced by his claim to be a champion grape picker, the good-natured dwarfs took pity on him because of his condition and allowed him to climb aboard.

Smyke found vineyards far more congenial than the wild woods of Zamonia. What was more, he discovered to his own surprise that he really could help with the harvest because, after a short time, his fourteen arms enabled him to pick many more grapes than a Midgardian dwarf.

He and his companions went from vineyard to vineyard, usually spending one day at each and then moving on. In this way they progressed north-westwards at a leisurely pace from Orn to Tentisella, from Nether Molk to Upper Molk, from Wimbleton to Moomieville, from Zebraska to Ormiston. To Smyke, physical exertion and a nomadic existence were entirely new experiences.

After a few weeks the convoy reached a major outpost of Zamonian civilisation in the vicinity of the Gargyllian Bollogg’s Skull, a rock formation reputed to be the petrified cranium of a giant. This district was also known as Grapefields because so many wine growers had settled there and transformed it into a veritable paradise for lovers of the grape. There were countless village inns and wineries, and a vast number of small vineyards that produced legendary yields. Grapefields was a fully developed tourist area, and by Smyke’s standards it came close to being as much of a heaven on earth as a genuine big city.

Bidding farewell to the simple life and the Midgardian dwarfs, Smyke now roamed around on his own. He lived on his meagre savings and an occasional game of cards. This was child’s play, because people on vacation in Grapefields had money to burn and were far from averse to the odd game of chance.

Smyke used his winnings to fulfil the visions that had kept him going at the bottom of his slimy pool on Roaming Rock: he lived out his culinary dreams in every detail. Some of the finest chefs in Zamonia had opened restaurants in the Grapefields area and Smyke patronised them all. He went through the menus from beginning to end and back again, until every memory of his privations had been effaced and converted into body fat. He had truly reached civilisation at last.

Smyke’s excursions had naturally taken him into the neighbourhood of the Bollogg’s Skull. Growing on its steep limestone slopes were wild vines that could be harvested only by the flying Gargylls who inhabited the caves inside the gigantic head. It was said that, many years ago, a frozen meteor from outer space had struck the Bollogg’s Skull and melted, filling it with the mysterious black water that was the main source of the fabulous wine for which the whole district was famed.

The truth wine

‘Gargyllian Bollogg’s Skull’, as the wine growers called their wine, was pitch-black in colour and as thick as molasses. It could not be said to possess any of the characteristics that normally distinguish a wine. It neither refreshed nor relaxed, was guaranteed to spoil a decent meal, had no bouquet or taste and was not even genuinely intoxicating. What rendered it so unique and sought after was that it allegedly induced a state of mind in which those who drank it learnt the truth about themselves. You couldn’t buy it in casks or bottles. It was served only by the glass, and at an exorbitant price, in one particular tavern situated at the foot of Bollogg’s Skull. Its name, logically enough, was The Bollogg’s Skull.

Smyke had already heard the Midgardian dwarfs talking about this wine – in fact, the subject always cropped up sooner or later in any conversation. The locals, who spoke of it only in mysterious and enigmatic terms, intimated that its effects weren’t to everyone’s taste. The longer Smyke spent in Grapefields, however, the more the wine intrigued him. And so, when he had won enough money at cards, he made his way to the aforesaid hostelry to sample it.

He felt a trifle uneasy when he reached the tavern at the foot of the gigantic skull. There were people who had strongly advised him not to touch the wine and one of his card-playing cronies had even claimed that anyone who got high on Gargyllian Bollogg’s Skull was never the same again.

But curiosity triumphed, of course, and Smyke ventured inside. The tavern was run by Greenwood Dwarfs whose hideous appearance created a rather uncomfortable atmosphere. Undeterred, Smyke loudly ordered a glass of the legendary beverage. The dwarfish waiter showed him to a table covered with a dirty cloth and promptly disappeared again.

Smyke sat down and surveyed his surroundings. All the customers were sitting by themselves at small tables, each with a glass of black liquid in front of him. Some were brooding in silence, others mumbling to themselves, and many pulling faces horrific enough to suggest that they were suffering from convulsions. A few were actually weeping. The place looked more like the recreation room of a lunatic asylum than the taproom of an inn. The Greenwood Dwarf returned with a glass of black wine, deposited it on the table and disappeared without a word.

Smyke took a cautious sip.

He felt cheated. The wine tasted of nothing, absolutely nothing, not even water. What a fool he was! He’d fallen for an old wives’ tale – for the oldest tourist trap in the district. Remembering how expensive the wine was, he decided to make a fuss when the waiter reappeared

. Perhaps he could get out of paying the bill. He looked up – and gave such a terrible start that he spilt the rest of the wine on the grubby tablecloth. Seated across the table from him was himself.

Smyke’s alter ego

‘No, your eyes don’t deceive you,’ said his alter ago. ‘It’s you. You’re me. I’m you. You’re looking at yourself.’

‘Heavens,’ said Smyke, ‘I wasn’t prepared for this.’ No, there was no mirror. It was his doppelgänger all right.

‘Nobody’s prepared for it, curiously enough. It’s only logical, though, when you come to think about it. After all, who is better qualified to tell you the truth about yourself than yourself?’

‘Man, oh man,’ said Smyke, fanning himself with several pairs of arms at once. ‘This is really incredible! I need some time to take it in. You look so real.’

‘I’m as real as you are. Have some more wine.’

‘No thanks, I’ve had enough. Any more and there might be three of us sitting here.’

‘It’s not like getting drunk. You can’t improve on your present condition. What you see is what you get.’

‘I might just as well have looked in a mirror,’ said Smyke. ‘It would have been cheaper.’

‘Yes, exactly. You’re seeing what you’d see in a mirror, but much quicker.’

‘How do you mean, much quicker?’

‘Wait and see. Look at me! Concentrate on me!’

‘You mean you’re going to show me something?’

‘I’m already doing so. Look closer.’

Smyke stared at his alter ego. Yes, it was himself, his exact mirror image. A trifle weary-looking, perhaps, but after all that had happened recently … But did he really look that old? Yes, he probably did by now. But … Just a minute! Those little crow’s feet beneath his eyes – surely they hadn’t been there this morning! Or had they? No, definitely not! This wasn’t a very good likeness of him after all. It was more like a poor imitation in a waxworks.

And this was supposed to be the real thing?

Smyke eyed the wrinkles suspiciously. Suddenly there were more of them. And more. Big bags were forming beneath the eyes of his alter ego.

‘Just a minute …’ muttered Smyke.

His alter ego grinned. ‘You’ve caught on at last, huh? It isn’t a pretty sight.’

Smyke had caught on all right. This wasn’t a poor imitation, it was a perfect likeness of himself in ten or twenty years’ time. He was watching himself grow older.

His alter ego’s skin was becoming drier, greyer and more wrinkled. Discoloured flecks appeared, warts took shape.

Smyke shivered. His alter ego grinned, baring its teeth. They were yellow and longer than usual. The gums receded and became inflamed, the necks of the teeth were exposed and turned brown. One rotten black stump detached itself from the pale, diseased gum and dropped off on to the table.

‘Whoops!’ said his alter ego.

This was going decidedly too far, thought Smyke. He was watching himself dying, not just growing older.

‘Stop it!’ he entreated, but he couldn’t tear his eyes away from the gruesome sight. His alter ego’s skin had creased into thousands of tiny folds, the face was puckering like an overripe plum, the hands and arms were little more than skin and bone. Then they, too, began to fall apart and drop off. Smyke could make out the individual bones and desiccated sinews.

‘Stop it, I said!’ gasped Smyke. He burst into tears.

‘No can do,’ said his ghastly doppelgänger. ‘The truth is inescapable. Well, it’s been nice having a drink with you, brother of mine. Just remember this …’ It leant forward, bared its rotting teeth in a frightful grin, and whispered ‘They’ll be coming to fetch you.’

Then it broke into a sinister laugh. It laughed until it choked on its own vocal cords. As the last peal of laughter died away the lower jaw came adrift and fell off on to the table. A grey tongue lolled from the open throat. Then that, too, fell off and exploded into a puff of dust. Smyke uttered a high-pitched cry.

A voice behind him said, ‘Can I get you something else, sir?’

He spun round. The dwarfish waiter was standing there, eyeing him malevolently.

‘What?’

‘Would you care for something else, sir? Some cheese, perhaps?’

‘Er, no thanks,’ said Smyke. He turned to look at his frightful companion, but there was no one there. The chair on the other side of the table was empty, the table itself bare of teeth and other detritus. The nightmare was over.

‘Yes, the truth is hard to endure,’ said the waiter. ‘Lies are nicer, we all know that, but it changes your outlook, seeing things telescoped like that. May I bring you the bill?’

‘Yes, please,’ Smyke said hastily, ‘and be quick about it.’

He waited, breathing heavily, for the dwarf to return. Sweat was oozing from every pore of his body. He paid the bill and the waiter escorted him to the door.

‘Just wait, you’ll soon feel better. The purifying effect takes time. You’ll feel newborn.’ The dwarf gave a frightful laugh. ‘It’ll change your life, believe me,’ he called as Smyke disappeared into the darkness. ‘Goodbye for ever! No one ever pays us a second visit!’

On the warpath

Smyke left Grapefields early next morning and set off. He had scarcely slept a wink all night. Even when he did doze off, all he saw were visions of his rapidly ageing self, who kept whispering, ‘They’ll be coming to get you.’

There was no time to be lost. He’d wasted so much of it on that accursed Roaming Rock! There were things to do apart from fleecing wine bibbers with a few cheap card-sharper’s tricks and using the proceeds to eat his way through the menu of every restaurant in Grapefields.

His other recurrent vision during the night was of Professor Ostafan Kolibri. Instead of horrifying him, however, it had filled him with hope. He now realised that he had instinctively headed in the same direction as the professor had taken when they parted. The knowledge with which Kolibri had infected him was having an after-effect the Nocturnomath had omitted to mention: Smyke wanted more of it. His thirst for scientific information had been whetted, and his store of knowledge was posing new and urgent questions which only the professor could answer:

If the readiness of Zamonian bees to discuss matters by haptic means were allied with the floral transmission of information, would it not be possible to develop an apiarist’s language capable of verbally stimulating their honey output?

If the surgical instruments in the Non-Existent Teenies’ subcutaneous submarine can start a dead heart beating again, to which parts of the anatomy should they be applied?

And if it were possible to start a dead heart beating again, would that not be a first step towards combating the inexorable fate so drastically demonstrated to Smyke by his alter ego?

Following in Kolibri’s footsteps meant defying fate and declaring war on death. And Smyke was an expert on war, for had he not been Prince Hussein Banana’s war minister? Yes, when he conjured up the vision of that puny, pigeon-chested gnome of a scientist, he clearly perceived that Kolibri needed a powerful ally in his fight against almighty death. It was Smyke’s wish – nay, his destiny – to follow the professor to Murkholm as quickly as possible.

Torrentula and the Demonic ferrymen

The further Smyke progressed through north–west Zamonia, making for the coast, the sparser the signs of civilisation became. The Arcadian landscape of Grapefields gave way to monotonous, almost deserted prairies inhabited by sheep farmers who were among the poorest members of the Zamonian population. Gone were the taverns and wine shops, and no one here was free enough with his money to risk it on a game of chance. Smyke occasionally happened on a farm where he could obtain a bed of straw and a meagre breakfast in return for a small sum, but in general he had to content himself with a diet of raw vegetables. As a result, his financial reserves and all the fat he’d put on in Grapefields gradually melted away like butter in the sun.

The

climate became steadily harsher. The everlasting east wind had scoured the landscape into a flat, featureless expanse, and bent every tree and blade of grass into submission. A thin drizzle fell without ceasing. Smyke knew that in Torrentula, the district through which several rivers flowed oceanwards from the Gloomberg Mountains, there were some small villages where so-called Demon Boats could be hired to take one further. Only the most audacious travellers availed themselves of this inexpensive form of transportation, for the Demon Boats were diminutive craft manned by ferrymen of semi-Demonic ancestry who always shot Torrentula’s dangerous rapids by night.

However, Smyke was becoming so sick of the monotonous scenery that he decided to take the risk.

The very look of the boat he boarded in one of the villages, which was criss-crossed by several small rivers, made an unnerving impression on him. It was coal-black and shaped like a grotesque Demonic head with horribly gaping jaws. He took his place in it accompanied by the ferryman, who was muffled up in a black cloak. Seated behind Smyke, he made not the slightest attempt to steer and spent the whole time cackling incessantly. At first they glided leisurely downstream, and Smyke had just concluded that the ferryman’s infuriating laughter was the worst feature of the voyage when the boat put on speed and the Demonic pipes mounted on the cabin roof began to wail in the wind. They proceeded to shoot the rapids at a rate of which Smyke would never have believed a river craft capable. Flung ever more violently to and fro by the current, the boat rotated on its own axis and stood on its head by turns, submerged completely, regained the surface and plunged down several waterfalls. Although unafraid of drowning, being a semi-aquatic creature, Smyke thought it quite possible that he would be smashed to pieces against the hull. Either that, or he would go insane with fear and join in the ferryman’s demented laughter.

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

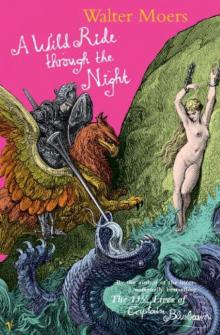

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night