- Home

- Walter Moers

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear Page 10

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear Read online

Page 10

A change sets in

Professor Nightingale’s lessons had undergone a change of some kind, and I’d recently found it difficult to follow him. Although the subjects were no harder and his lectures as fascinating as ever, I simply couldn’t take them in any more. No sooner was school over for the day than I lost all recollection of what I’d been taught.

I sometimes caught myself not listening at all and allowing my thoughts to stray. On such occasions, when subjected to a keen glance from Professor Nightingale, I would feel guilty. Although I still solved differential equations in my head after school, it seemed to me that I was growing steadily more dim-witted.

Knio and Weeny

After a short time the Nocturnal Academy acquired some more new pupils, two rather uncongenial individuals named Knio and Weeny.

Knio was the last surviving representative of a species known as the Barbaric Hog, which really says it all. He had more muscles than a plough horse and incredibly bad manners. When you were talking to him he either kept punching you or slapped you on the back with one of his fat trotters. He had short, greasy hair, foul breath, and – although he was only eight years old – a bad case of five o’clock shadow. He was continually uttering oaths in which prominent roles were played by all manner of gods, giants, or other legendary creatures. ‘By the Midgard Serpent!’ he would cry, or, ‘May the Megadragon devour me if it isn’t true!’ When we were in bed at night he used to torment us with his prodigious flatulence, of which, to crown everything, he appeared to be proud. ‘Watch out,’ was the customary prelude to one of his phenomenal farts, ‘here comes Wotan’s revenge!’ The rest of us would pull the covers over our heads and hold our breath until the worst was over. It would have been pointless to remonstrate with Knio because he was stronger than any of us now that Fredda had gone.

Weeny was a Gnomelet, the last of that family of miniature cyclopses. Gnomelets were a rather degenerate form of cyclops, neither strong nor awe-inspiring nor possessed of any other notable cyclopean attributes, but disagreeably pushy, sneaky, cowardly, lazy, arrogant, covetous, and greedy. Weeny was also short-sighted, not that he could help that. He kept fixing people with his single, piercing eye, which didn’t exactly add to his charms.

It was amazing how many obnoxious qualities could be accommodated in such a small body. Weeny always insisted on talking big although he had little to say, for his intellect was barely more developed than Knio’s. He was the kind of miniature cyclops that picks a quarrel, then hides behind someone bigger and stronger and incites him to violence. Looked at from that angle, Knio and Weeny were the worst possible combination.

I lose my one remaining friend

When Qwerty finally had to quit the Nocturnal Academy, my world almost collapsed. From then on I became a stranger among strangers.

‘It’s an absolute certainty that we’ll never see each other again,’ said Qwerty, when bidding me farewell. ‘I intend to throw myself into the first dimensional hiatus I can find, and the odds against our meeting again will be 460 billion to 1!’ – ‘No,’ I replied, having swiftly worked out this statistical problem in my head, ‘463 billion to 1.’ It really was extremely unlikely; the chances of winning the lottery 15,000 times in succession (with tickets bought at the same counter) were, in fact, greater. I silently shook Qwerty’s gelatinous hand. Then Professor Nightingale conducted him to the exit tunnel. After that, my sojourn at the Nocturnal Academy became steadily more unendurable. Even the lessons had become a torment. It no longer interested me to hear what Professor Nightingale had to say about the crystalline structure of snowflakes, the habits of the Andean lama, or the brushwork of the calligraphers of the Eastern Incisors. His pearls of wisdom ran off me like water off a duck’s back. I had reached the stage where I no longer understood what he was talking about – in fact I sometimes felt he was speaking an entirely unknown language.

Another philosophical debate

Still more of a trial, however, were the evenings I spent with my new classmates. Their standard of education was shockingly low. They were just getting to grips with multiplication and capitals or lower-case letters, whereas I was debating major problems of astrophysics in my head. One night, Knio and I had an argument about the nature of the universe. He had an appallingly crude conception of the physical world.

‘The earth is a bun floating in a bucket of water,’ he asserted defiantly.

‘And what is the bucket standing on?’ I demanded, trying to floor him.

‘The bucket stands on the back of the Great Cleaner who polishes the universe to all eternity,’ Knio replied self-confidently.

‘This universe she polishes so assiduously,’ I said, ‘what in the world does that stand on?’

‘The universe doesn’t stand on anything, it lies,’ Weeny put in.

‘The universe is as flat as a slice of sausage, you see.’

‘And what, pray, does the slice of sausage lie on?’ I had him now!

‘On the bun, of course,’ replied Knio.

You simply couldn’t have a rational argument with such barbarians.

To take my mind off Knio’s farts, Flowergrazer’s lamentations and Weeny’s bragging I had developed the habit of solving philosophical riddles that had never been solved before. One night, when sleep had eluded me yet again because a philosophical problem was preying on my mind (I was reflecting that I was bigger than Weeny, so I was big; at the same time, however, I was smaller that Knio, so I was small; but how could I be big and small at the same time?), I passed Professor Nightingale’s darkroom on my way to the canned sardine store.

The professor’s darkroom

A terrible splintering sound penetrated the heavy door and went echoing along the passage. Whenever the professor was pondering an especially ticklish problem, he made a noise like a nutcracker demolishing a large walnut. This noise issued straight from his brains, a fact that impressed me on the one hand but gave me the shivers on the other. I was about to tiptoe on when a loud ‘Come in!’ made me freeze in mid movement.

No pupil had ever been privileged to set foot in the professor’s mysterious domain. I was beginning to think I’d made a mistake when I heard Nightingale’s voice a second time.

‘Come in, but don’t let any light in!’

On opening the door I felt as if the darkness were flowing over me like molasses. ‘Come in and shut the door!’ Nightingale commanded, so I obediently tiptoed inside.

The gloom that enveloped me when I shut the door behind me was so absolute that I got the wind up. It was a darkness I could feel on my skin, the way I’d felt it on Hobgoblin Island when, for the very first time, I spent a night without any lights on. But this darkness was audible as well. It gripped me like an icy fist, making a humming sound so faint and despairing that my fur stood momentarily on end.

I hadn’t been in the chamber for more than a few seconds when I got the feeling I’d been blind since birth and had no idea what light was. I groped for the doorknob, but I didn’t even know where ahead or behind were, still less up or down. I felt I was floating in starless space, weightless and utterly alone.

‘Don’t go!’ Professor Nightingale said sharply. ‘One gets used to it.’

I hadn’t the slightest notion where he was. My dearest wish was to run for it, screaming in terror, but I strove to remain polite. ‘It’s, er, very dark in here,’ I understated.

‘Poppycock!’ barked the professor. ‘The ambient lighting registers four hundred nightingales.’

The ‘nightingale’, I knew from my lessons, was a unit of luminosity invented by the professor himself (modesty wasn’t his long suit). A nightingale corresponds roughly to the light prevailing on a starless night during a lunar eclipse. To take a more down-to-earth example, the interior of an airtight refrigerator registers (when the door is shut and the light has gone out) precisely one nightingale. Thus, a luminosity of four hundred nightingales was equivalent to the darkness prevailing in four hundred closed refrigerators. It was

correspondingly cold as well. ‘The nightingalator is running at only half speed. I’ve even blindfolded myself because I find the light too bright.’

Nightingale removed the blindfold. I could tell this because his eyes glowed in the dark like a pair of searchlights. A Nocturnomath’s eyes always glow, even in daylight, but the effect was far more impressive in absolute darkness, perhaps because of the brains revving away behind them. Caught in their beams, I somehow felt guilty.

‘Why creep around in the middle of the night, eh?’ the professor demanded, playing the twin beams over my face.

‘I, er, couldn’t get to sleep because I, er, couldn’t get a philosophical problem out of my head. I was turning it over in my –’

‘Nonsense!’ Nightingale brusquely cut me short. ‘You couldn’t get to sleep because Knio, that antediluvian idiot, pollutes the air with his barbarous expulsions of wind! You couldn’t get to sleep because you can’t take any more of your classmates’ childish chatter. You couldn’t get to sleep because you miss your conversations with Qwerty and Fredda.’

The old man knew simply everything. He shook his head, and the beams from his eyes roamed the room like those of a lighthouse.

‘You’ve been here too long … Now your time is up. One moment, I’ll switch off the nightingalator …’

The nightingalator

I heard a series of faint, mysterious clicks and it slowly grew lighter. Although the lighting that now prevailed would undoubtedly have been described as dim under normal circumstances, I found it quite bright after the darkness that had preceded it. I could at least distinguish the outlines of the curious apparatus Nightingale was tinkering with.

It looked like a factory in miniature, or rather, like several little interconnected factories with countless tiny smokestacks and boilers, cables and cogwheels, pumps and engines. There were bellows rising and falling, pistons sliding in and out, little chimneys that emitted occasional jets of flame, and air shafts with black steam issuing from them. (The reader may, perhaps, object that black steam doesn’t exist, and that I’m confusing it with black smoke. I must nonetheless insist that the odourless water vapour issuing from the nightingalator was black as night itself, not white.)

I even thought I discerned some shadowy little figures flitting around on the iron stairways and catwalks, miniature factory workers carrying tiny spanners, but that, I’m sure, was just my imagination. The mechanical pounding gradually slowed but never ceased entirely.

‘What exactly is a nightingalator?’ I ventured to ask.

‘A nightingalator,’ the professor proudly and promptly declared, as if I’d pressed a button in his chest, ‘is a darkness-manufacturing machine invented by myself. With the aid of the so-called nightingalasers generated by this wonderful contraption, exceptionally dark, starless patches of night sky can be cut out and transported straight to this chamber, where the nightingalator stores and refines them. This enables me to bottle the darkness like wine from a cask. I can also condense or dilute it as required. A triumph of darkness research – or nightingalology, as it is termed by experts in this scientific field.’

The sole expert in this field, of course, was Nightingale himself. It was only then that I spotted the big telescopic tube projecting from the nightingalator to the ceiling. Unlike a normal telescope, this one had a kind of knot in the middle. In the ceiling I made out an aperture that could be closed like a camera’s diaphragm. It must have led to a shaft through which the night sky was visible.

‘The darkness in here,’ I said for something to say, ‘does it come from outer space?’

‘It does indeed, my boy. You won’t find denser darkness anywhere – it’s the eternal blackness of the universe! Did you know that ninety per cent of the universe consists of dark matter? No one has ever been able to observe it until now. Its existence could only be inferred from its gravitational effects, but I, with my nightingaloscope, have discovered and isolated it!’

The nightingaloscope

He gestured grandly at the telescope.

‘Whenever you look up at the stars, you’re seeing the past. The light of the stars you see in the firmament is millions or even billions of years old. People are always talking about the light of the stars, but the darkness between them is just as old – indeed, much older as a rule, and there’s far more of it! Darkness ages like wine: the older it is, the better. The darkness in this room is nearly five billion years old – an exceptionally fine vintage.’

He sniffed and smacked his lips like a connoisseur sampling an expensive bottle of claret.

‘I won’t overtax your brain with details, my boy – besides, it’s a top secret matter. All I can tell you is that I’ve invented a sophisticated system of prisms, lenses and mirrors that enables me to bend my nightingalasers in space and send them through a wormhole!’

He sat back complacently, fitted his fingertips together, and twiddled his thumbs like a barrister who has just presented the judge with a cast-iron alibi.

A wormhole, to quote a standard item of knowledge in the Nocturnal Academy’s syllabus, was a kind of short cut through space, a secret tunnel in the space-time continuum through which very distant points in the cosmos could be reached more quickly than usual. If I had understood him correctly, Nightingale was saying that he’d sent his lasers on a sort of time-warp journey through space.

‘And that’s not all!’

He indicated another part of the nightingalator – one that resembled a mechanical hedgehog.

‘My rays are capable of cutting out sizeable chunks of cosmic darkness. Then, with the aid of this retromagnetic particle vacuum cleaner (the Nightingale 3000, patent pending) I can suck the said material straight out of the universe! Imagine, darkness direct from the furthest corner of the cosmos, vacuum-packed for millions of years, here on this very table! Darkness can get no darker!’

The professor emitted a grunt of triumph.

Black holes

‘All the cutting process leaves behind in the sky are holes so abysmally dark that they annihilate light itself. Future generations of scientists will rack their brains over the source of those black holes, tee-hee!’

He said no more for a while, just grunted to himself in an absent-minded way.

‘But I still haven’t found a way of putting this dark material to good use,’ he growled. ‘It’s here, but it has no practical applications – it’s so damned negative!’

He lapsed into a brooding silence.

I felt I ought to say something encouraging.

‘Perhaps the material must first get used to its new environment. I well remember my first week in the Gloombergs. I myself felt –’

‘Pooh!’ the professor cut in brusquely. ‘What do you know about the mysteries of the universe?’

He was right – what did I know about them? My brain really was feeling rather overburdened with details. Having made enough of a fool of myself already, I thought I’d better bow out as gracefully as possible.

‘Well,’ I said as I edged towards the exit, or what I took to be the exit, ‘it’s getting late. I won’t intrude on you any longer …’

‘The door’s in the opposite direction,’ Nightingale murmured vaguely. Then a sudden thought seemed to strike him.

‘No, don’t go! Stay here – please,’ he said in an uncharacteristically polite and gentle tone. ‘We could have a bit of a chat.’

This was a novelty. Nightingale had never conversed with me before – he never conversed with anyone on principle. To him, a conversation meant that he held forth while others greedily absorbed his pearls of wisdom. He welcomed the occasional timid question because it gave him a chance to deliver another lengthy monologue, but he disliked empty chatter. Nocturnomaths hate conversations.

‘You’ve probably been wondering how you’ve managed to learn so much in so short a time,’ Nightingale began.

‘Perhaps I’m exceptionally gifted?’ I hazarded rather incautiously. ‘Gifted? Pooh, nonsense!’ he

barked, so loudly that I retreated a step.

Intelligence bacteria

‘Forgive me …’ He lowered his voice again. He was simply unused to holding a normal conversation, but he was doing his best. ‘Does Knio strike you as gifted? That porcine blockhead has a brain the size of an atomic nucleus. When the lights go out he thinks the world around him ceases to exist, but by the time I’m through with him he’ll be knowledgeable enough to construct a submarine blindfolded or discover a cure for the common cold. It’s nothing to do with brains, it’s bacteria.’

‘Bacteria?’ I knew, of course, that bacteria were minute organisms capable of transmitting diseases.

‘Precisely. You must simply conceive of knowledge as a disease – a disease we Nocturnomaths transmit. The closer a person comes to a Nocturnomath, the more knowledge he becomes infected with. Take a step towards me.’

I did so, although I was far from reassured by the thought that he was a source of infection. I had never been as near him before, not even in class.

‘Closer!’ Nightingale commanded.

I took another step, and suddenly a tide of information surged through my brain. It was all to do with darkness research, a subject I had never studied in any detail. All at once, I felt I was an expert in that field.

‘So tell me,’ the professor demanded, ‘what do you now know about darkness?’

‘Oh, it’s all quite simple once you rid yourself of the preconceived idea that darkness is merely the absence of light,’ I was astonished to hear myself say. ‘You have to learn to treat light and darkness as energy sources of equal status.’

‘That’s just the trouble,’ Nightingale put in. ‘The thing is, darkness has such a bad reputation. People always associate it with unpleasant things, but it’s simply another – albeit darker – form of luminosity. We need it quite as much as we need light. Without darkness everything would wither and die. There would be no sleep, no relaxation, no energy, no growth. Night gives us the strength to withstand the rigours of the day. Haven’t you ever wondered why we feel so refreshed and full of energy after a good night’s sleep?’

The City of Dreaming Books

The City of Dreaming Books Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures

Rumo: And His Miraculous Adventures The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books

The Labyrinth of Dreaming Books The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear

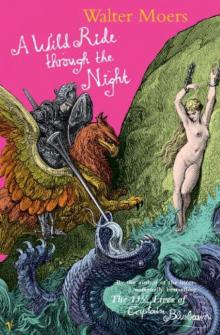

The 13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear A Wild Ride Through the Night

A Wild Ride Through the Night